Part 1: The bygone Golden Age

There is a paradox at the heart of life in the digital age.

Despite what we often see in the headlines about politics or the economy, in most ways of measuring life outcomes, people in the U.S. and much of the world are living better today than ever before. Americans are living longer and healthier; are more educated; have plentiful and varied food supplies; live in bigger and safer homes; experience a cleaner and greener environment; work in safer workplaces; are less likely to suffer violence and accidents; collect incomes that are higher while absolute poverty is lower. Globally, human rights are expanded; more countries are democracies; income inequality is down as is warfare between states. However, not everything is better for everyone, everywhere, all the time. Yet in the aggregate, much of humanity is at the pinnacle of a march towards better living.

But we don’t experience life in the aggregate. We experience life specifically, uniquely, personally. Not as an average but as a point. And many people’s experience of life today is not that of a pinnacle of progress. It is, day in and day out, a feeling of inexplicable unease, a sense of unending challenge, a fear that things are perhaps more dangerous, the sensation of being constantly overloaded and ceaselessly stressed. By one measure, 40 million U.S. adults have some form of anxiety disorder. And 71% of Americans surveyed say they are dissatisfied with the way things are going.

This Entefy research attempts to answer the question at the heart of the paradox of prosperity: Why is our day-to-day experience of life out of sync with data telling us things are going so well? The answer starts with some important relationships. To achieve the improved outcomes we collectively and individually desire (longevity, wealth, health, etc.), we have to generate increased prosperity; to generate increased prosperity, we have to be more productive; to be more productive, we have to make changes that accomplish more; and when a lot of changes takes place at once, the result is increased complexity. You might say that we purchase better life outcomes using the currency of complexity.

In seeking to explain the disconnect between objective data and subjective experience, we analyzed information from 45 different sources—everything from the U.S. Census Bureau and Bureau of Labor Statistics to polling firms like Gallup—covering the decades from the 1950’s until today. This report is divided into 4 parts.

In Part 1, which continues below, we start decades back in time to examine that communal feeling of widespread success that today sometimes feels part of a bygone Golden Age.

In Part 2, we will define complexity, put some measurements around it, and evaluate the familiar and surprising ways it impacts our lives today.

In Part 3, we take a data-driven look at our shared confidence in society’s institutions.

In Part 4, we analyze changes to the structures of families, friends, and communities as well as changes to income and education.

Where we end up might surprise you because merely pointing out the challenges of modern life is not the goal here. It is simply the first step in identifying ways for each of us to participate more fully in modern progress. When we understand the paradox, perhaps we can break through it and start enjoying better, more fulfilling lives.

From team owner to team captain

At the end of World War II in 1945, the United States found itself the single largest country with its industry and economy still intact. But that economy was structured for war-fighting purposes. Soon after the war, slowly at first and then in earnest, the nation embarked on a 25- to 35-year period (up to roughly 1980-1990) in which we systematically dismantled the regulatory structures put in place during the War years.

During this period, the country largely eliminated price controls and capital controls. We deregulated the rail industry, the trucking industry, the airline industry, the shipping industry, the telecommunications industry, the financial services industry, the healthcare industry, and the energy industry. This strategic deregulation permitted greater competition, which in turn accelerated investment and innovation. Strategic deregulation was complemented by tactical regulation, which strengthened areas like product safety standards, consumer protection, and labor law.

Because we emerged from the War with a functioning economy, the U.S. began the post-War period with significant momentum driving its economic expansion compared to most other major economies. Deregulation further accelerated that growth during the 1970’s through the 1990’s. All told, the U.S. would sit atop the global economic ladder and experience 50 years of steady economic growth, interrupted only by temporary periods of recession.

Importantly, the benefits of post-War growth—the living experience of it—were enjoyed by most everyone. There was inequality but generally speaking most boats were floating higher on a rising tide.

Another factor contributing to post-War prosperity was the culmination of the accumulation of science and technology innovation across most economic sectors that took place over a 100-year period beginning around 1870. Throughout this time frame, transformative scientific discoveries were made in fields as diverse as pharmaceuticals, metallurgy, agrichemicals, electronics, biology, and physics. This broad tide of innovation drove great increases in productivity.

After 1970, innovation became increasingly restricted to the high technology and communication industries. While innovation was and continues to be dramatic in these two fields, these two sectors account for just 7% of U.S. GDP. At the same time, the pace of innovation in other key sectors such as agriculture, finance, and transportation slowed dramatically. Innovation continues, but many industries today sit atop their S-curves with their inventive heydays behind them.

During the 50-year period following the War, it was reasonable to conclude that the U.S. held a special and unique place in the world. It was easy to take for granted the multiple circumstances that created so much prosperity for so many, so quickly. Our corporations grew ever-larger, employing more and more people, and delivering to them more and more comforts. We reached the moon and defeated Communism. We conquered or contained centuries-old diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, cholera, typhus, and malaria. Our universities were unrivaled, our scientists provided a constant flow of amazing discovery. At any point along this timeline, the future looked bright.

Today, much has changed. Broad-based, easy gains in productivity may be behind us. We have to make harder choices. We have to live within constraints we did not anticipate or wish to acknowledge. There is more competition within our country and among global competitors. Digitization, the Internet, chip designs, and artificial intelligence are disrupting all our other industries. The U.S. still holds a unique and commanding position but the global order is disrupted and unpredictable. Our collective sense of exceptionalism has been upended by clear signs that we are one among many.

Which brings us to the paradox that defines life in the digital age.

The paradox of prosperity

Let’s restate the paradox of prosperity: despite pervasive evidence that life today is better than ever before in history, our subjective experience of life can feel—take your pick—unsettled, uncertain, or just plain anxiety-riddled.

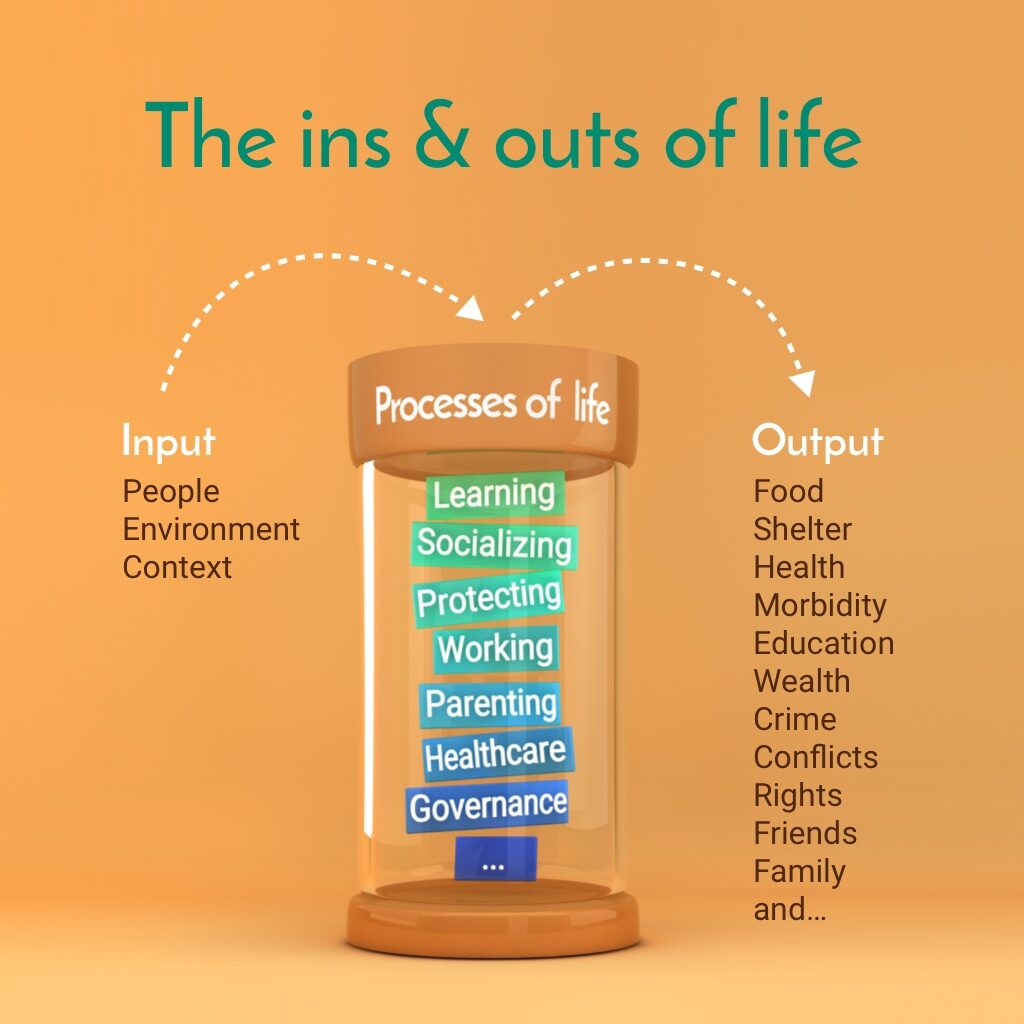

How do we reconcile these contradictory ideas? The first step is to establish a credible description of the problem. Matt Ridley, a former editor of The Economist, did just that in a speech to the Long Now Foundation entitled “Deep Optimist,” a great starting point on this topic. If we acknowledge that life has improved in general, what is the basis for all this pessimism? The answer begins in the abstract. Picture life as a black box with inputs, processes, and often unpredictable outputs. It looks a little like this:

Life’s inputs are people, environment, and context (an individual’s circumstances at birth and beyond). The processes of life influence and transform people’s lives, everything from parenting and education to employment and law. These processes impact the outputs: your quality of life. When we talk about the evidence that life today is better than ever, we are talking about measurements of these outputs, everything from GDP to educational attainment to average lifespan.

As we presented above, outputs have improved across the board for most Americans and for many around the globe. If all the outputs have improved, perhaps the perception of life’s difficulties and challenges reside within the processes that generate the outcomes—learning, socializing, protecting, working, parenting, healthcare, governance, and so on.

The sense of generalized anxiety so many people experience is a byproduct of the very complexity that emerges from increased productivity. We have access to incredible amounts of information to solve very targeted problems but this same ocean of information threatens to drown us. With greater complexity, we are less in control.

To dig deeper, we need to look at a representative example of complexity then and now. Let’s use the example of financing the purchase of a home in 1970 versus today.

To buy a house in 1970, you had to save enough for a down payment and then select from two choices of mortgage: a 15-year fixed-rate mortgage and a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage. Then, as it is now, that decision was monumental and consequential because a home is typically the single largest investment most people make in their lives.

In 1970, while your choice was simple (basically two mortgage options), it was also constrained. You had to have enough money saved for a sizable down payment as well as closing costs. You had to document a steady and secure income and an unblemished credit record. It was difficult to get a mortgage back then, with fewer mortgage lenders from which to borrow. Fewer choices and less risk.

In 2017, you have many more choices of a mortgage: Fixed Rate, Adjustable Rate, and Balloon Mortgages as well as 10-, 15-, 20-, 30-, and 40-year terms. There are many more providers than there were then, supplemented with countless mortgage brokers and online services. There are many options in down payment rules and credit requirements. It is much easier to borrow more than you can afford these days. What was a simple choice in 1970 has turned into a series of rather complex decisions for you to make.

Importantly, the consequences of poor decision making are now far greater than they were back then. It was much harder to get a mortgage in 1970 because the requirements were more stringent. But because they were more stringent, you were also much less likely to default with all the negative consequences that creates.

This change in consequentiality became tragically apparent in 2008 with the bursting of the real estate bubble. Millions of families lost their homes or declared personal bankruptcy for many different reasons but often simply because they had not properly understood the liabilities and risks of their mortgage decisions. Complexity and ambiguity created financial chaos that nearly collapsed the global economy.

Mortgages are just one example. You can see the same dynamics of complexity in college education (where to study, what to study, how to pay for it). Or in health insurance (HSA, PPO, HMO, HDHP). Or just select from the 39,500 different items in the average grocery store. The list goes on and on.

Common threads run through all of these examples. What you find is that today we have more choices, the context surrounding decisions is more volatile (past assumptions are not always reliable), there is greater uncertainty (not because of an absence of information but often because of an overabundance of information), and greater ambiguity (more fine print and nuance in terms).

Now, add isolation to this complexity. People in general have fewer friends and family members to call upon for advice and support, making us more responsible for our own lives than ever before. Family sizes and close friendship circles are smaller, church attendance is down—important because these institutions traditionally provided a buffer against life’s unanticipated setbacks. We are on our own in a world that is often volatile, uncertain, confusing, and ambiguous. Or at least that’s how it feels to a lot of people a lot of the time.

And so we find that, without intending to, we have collectively made a Faustian bargain. Across practically every area of life, we have more options to choose from and greater flexibility in achieving what we want. But at the same time we also bear a very real burden of greatly increased responsibility for the outcomes of those choices.

Part 2 of this report continues Entefy’s analysis of the Paradox of Prosperity. We’ll look at what decades of polling data reveal about the impact of complexity in our lives.