Entefy’s research into the complexity of modern life continues below. In Part 1: The bygone Golden Age, we outline the paradox of prosperity, the observation that despite widespread evidence of the world’s progress, our individual experience of life is often something quite different. In Part 2: Defining modern complexity, we analyze the aspects of life today that create the experience of complexity and consequentiality. In Part 3: The general erosion of confidence, we look at the evolution of our collective trust in social institutions. In Part 4: Family, friends, and community, we analyze the structure of social circles and changes to income and education. The report concludes by examining how digital technologies can contribute to meaning and fulfillment in modern life.

Part 2: Defining modern complexity

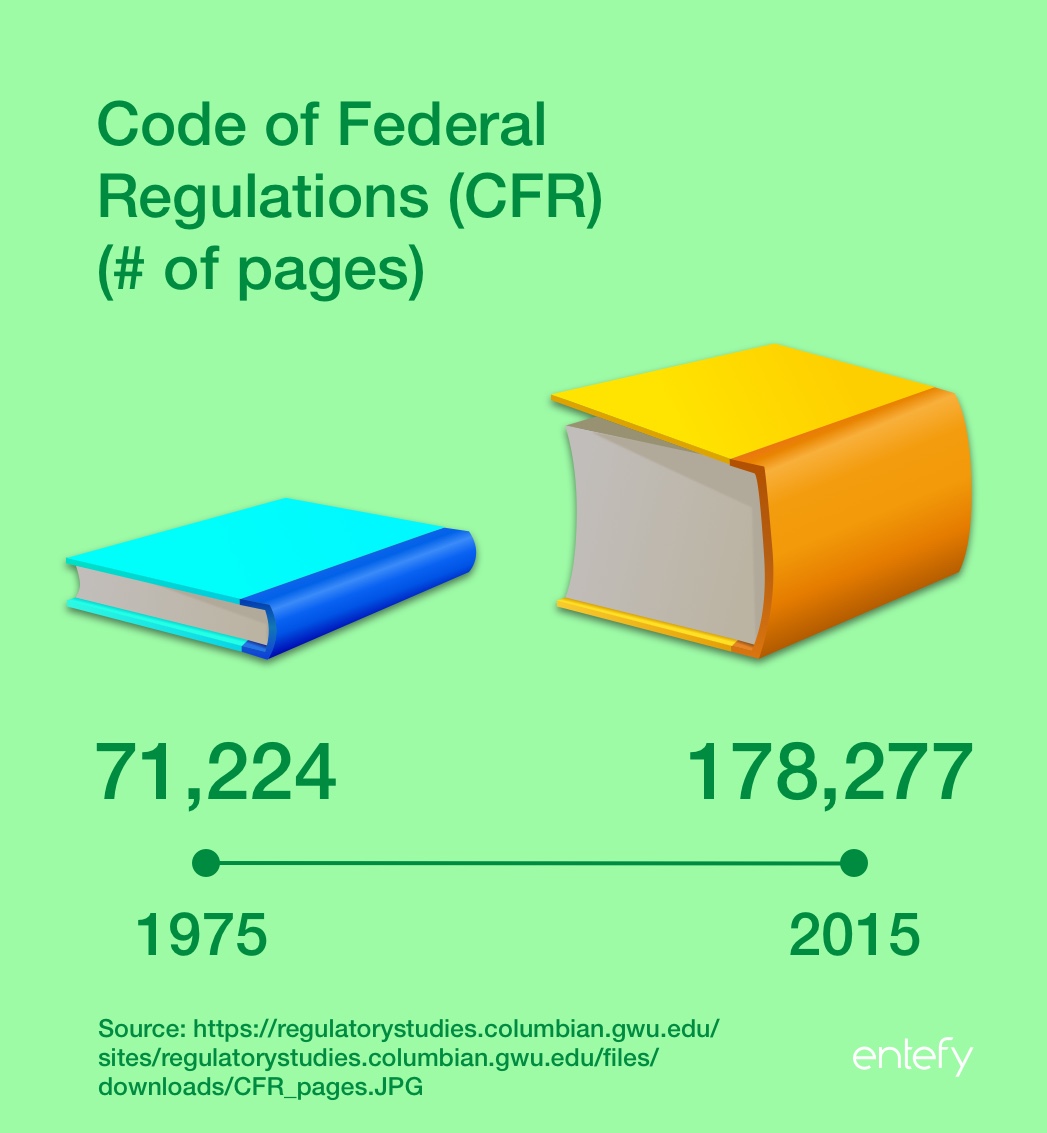

Complexity is central to the paradox of prosperity. It emerges from the rapid pace of change, and the arrival of seemingly endless choices in practically every area of life. But not just the number of choices we face. It’s the number of choices we make that carry great weight and consequentiality, yet are made with little outside support.

This pattern of choice and consequentiality can be seen in many areas of life. We are more responsible for our own retirement saving than in the past, as demonstrated by the decline of employer-provided pensions and the rise of personally-managed savings accounts like 401(k)s. Similarly, education choices are greater as are their costs. Healthcare planning is more complex and driven by our own choices.

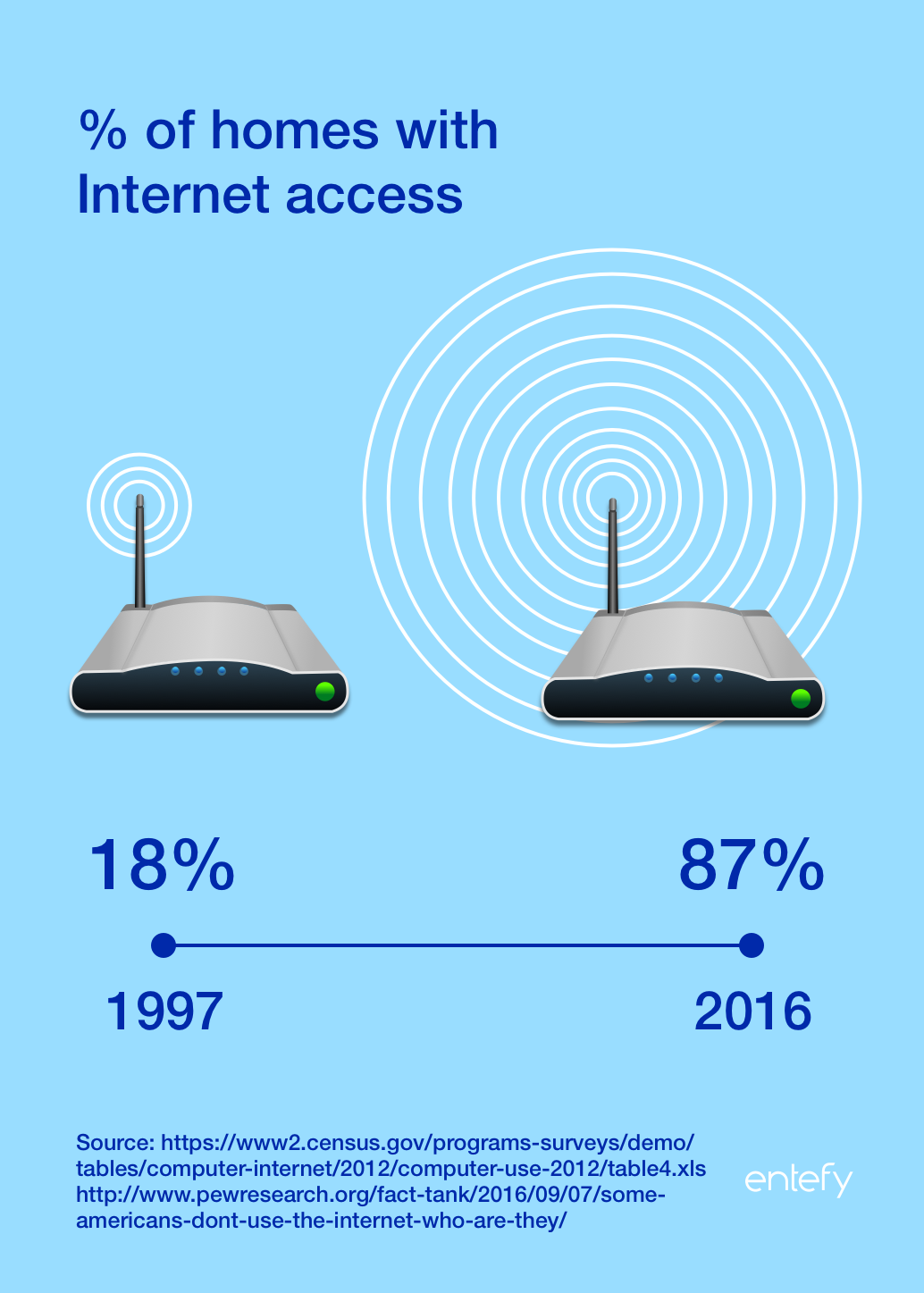

And nowhere is complexity and the pace of change more apparent than in digital technology. To take just one example, there’s the increasing complexity and volume of communication that occurs in our connected worlds. Digital messaging technologies allow astounding opportunities for personal connection, independent of time and space. Yet the technologies have also created very real obligations in terms of hours in a day and number of emails, phone calls, text messages, and the like. When you consider that just 10 years ago, the first smartphones were hitting store shelves, the pace at which we’ve adjusted our lives to accommodate their capabilities is astounding.

Financial planning, education, healthcare, and technology are not carefully selected examples. We see the same dynamics of complexity throughout our day-to-day lives. Here are some more concrete manifestations of increased choice and consequentiality.

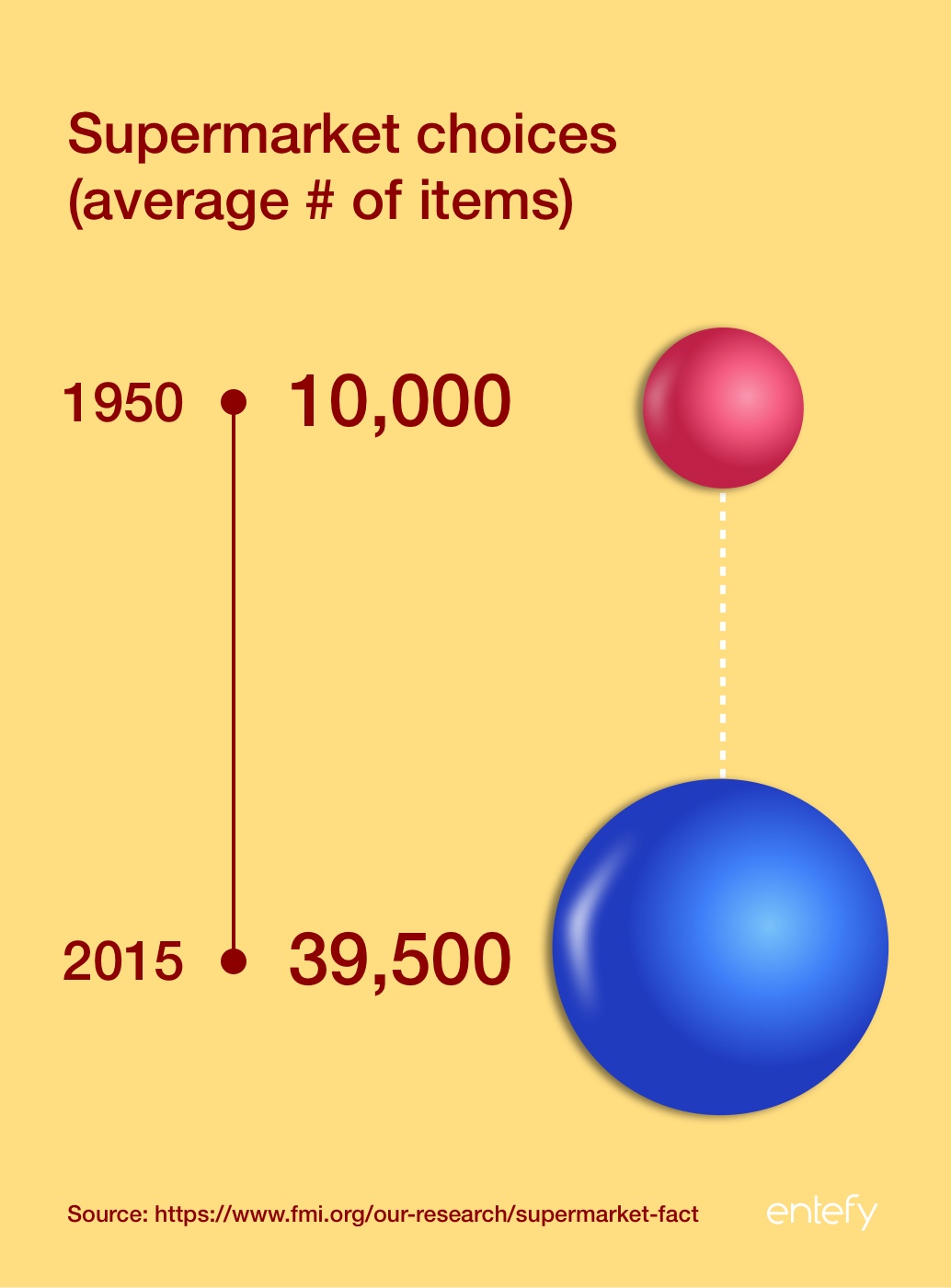

It is important to note that, for example, the 4x increase in items in the supermarket is neither inherently good nor bad. In fact, choice in life is generally considered a positive—until it overwhelms us and leads to analysis paralysis.

As the data suggests, today’s world for the most part offers us more choices.

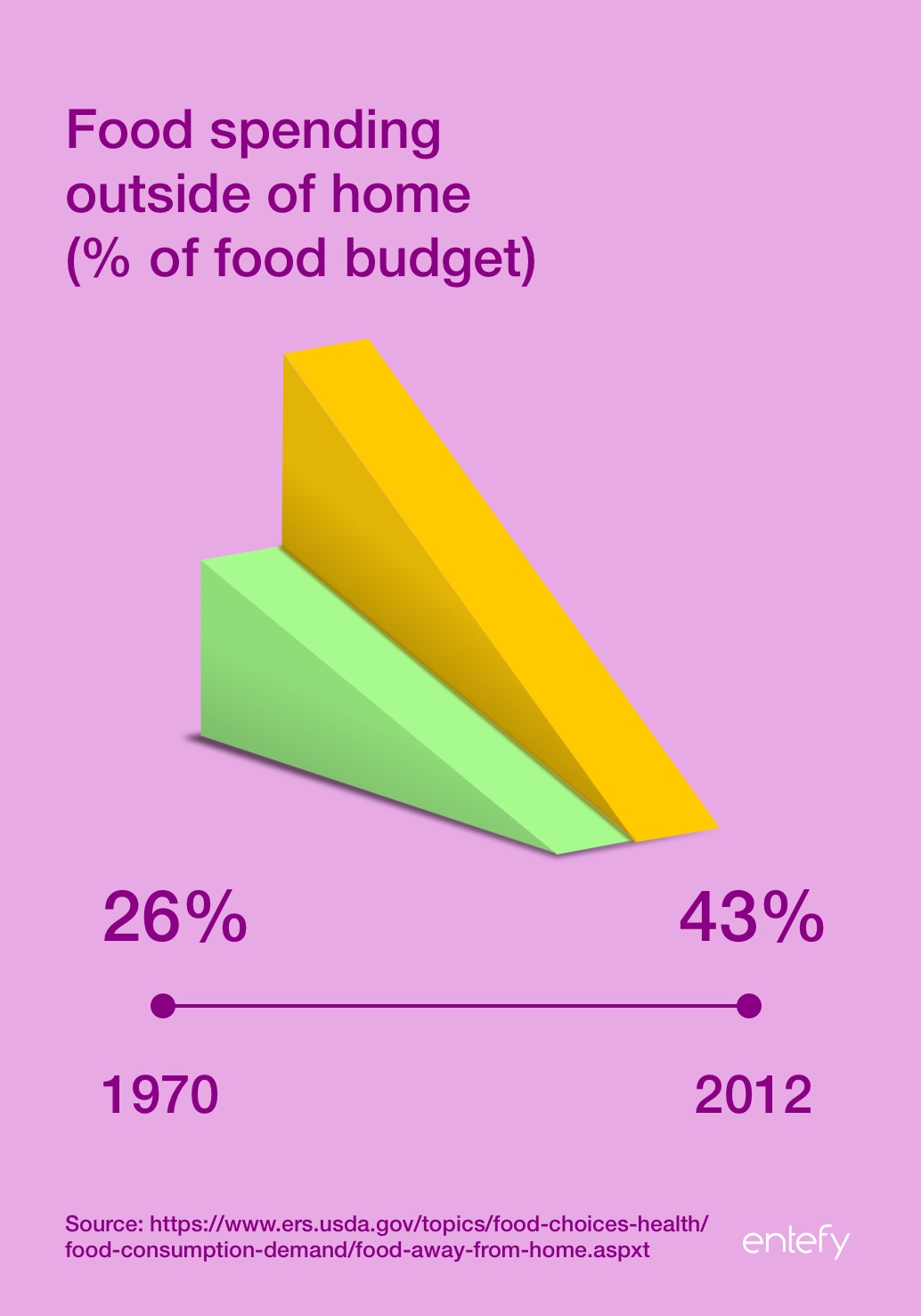

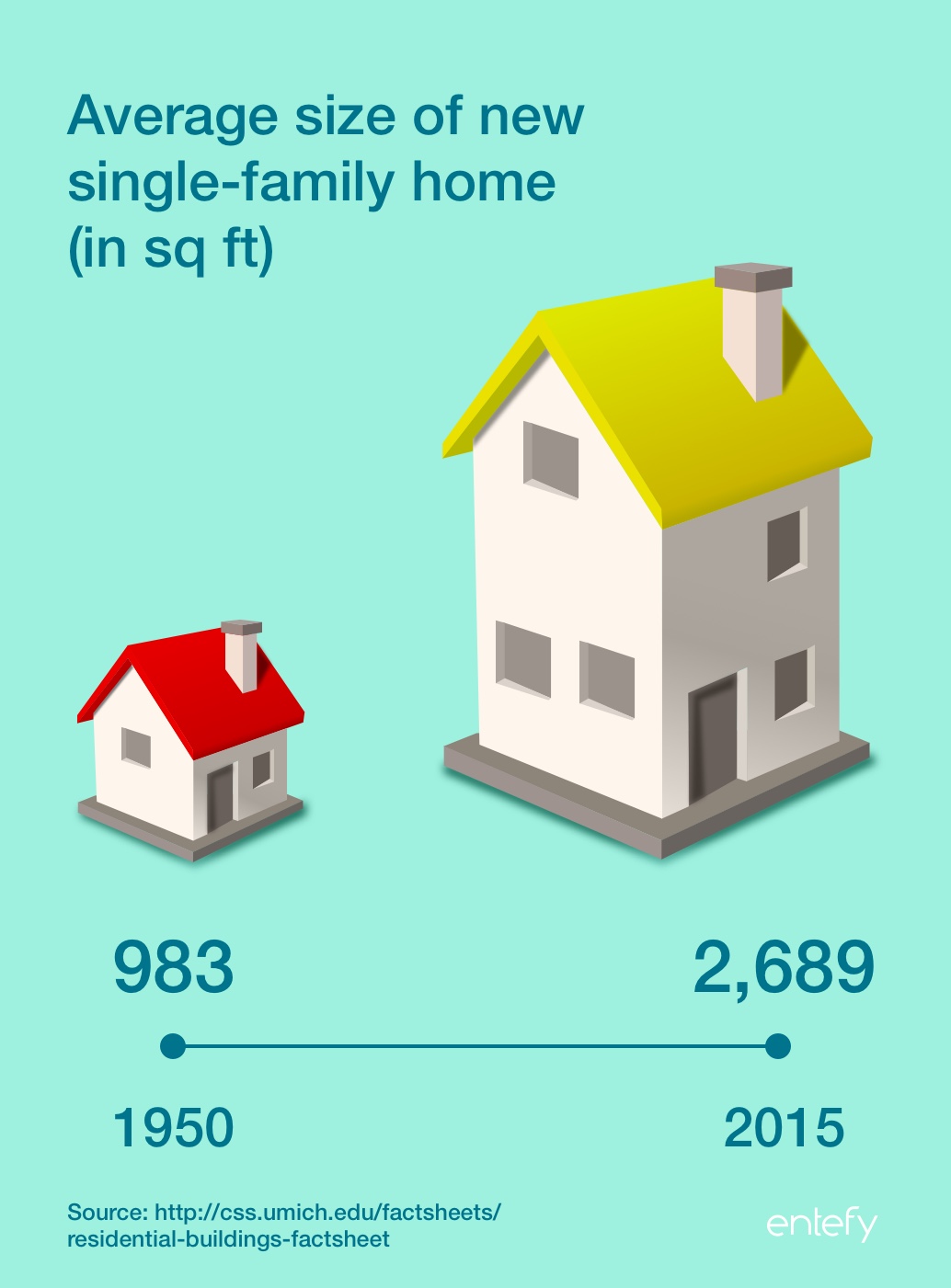

We have more items to choose from at the grocery store, we dine out more often, we live in larger homes, and those homes are equipped with more labor-saving and electronic devices than before.

The number of unique items for sale in a typical grocery store rose nearly four-fold between 1950 and now. This is a good thing in terms of increased choice. However, it is a challenge in terms of efficiency. Here’s an example: You are sent to the grocery store to “pick up an extra package of spaghetti.” You get there and discover that you have a dozen brands to choose from, you realize you don’t know the difference between n. 8 and n. 9 spaghetti, and you aren’t sure whether to buy the regular or gluten-free version. The consequences aren’t grave in making a bad decision. But a decision has to be made nonetheless.

Eating out is a pleasant indulgence but again: “Where do you want to eat?” “I don’t know, where do you want to eat?” This is trivial, until you add up all of the time we spend making all of these decisions.

Homes that are 2.7x the size of those in the 1950’s represent a rising degree of prosperity but that extra space also means more decorating decisions, more decisions about home security, energy consumption, furnishings, and so on. A corollary to home size is the number of electronic devices. Not just straightforward things like a TV or a computer but also a microwave, an alarm clock, a thermostat, a speaker. Each one of these electronic devices has attendant complexities – whether to buy a warranty, learning how to use it, figuring out how to connect one with another. We take much of this day-to-day complexity for granted, but there are hidden costs.

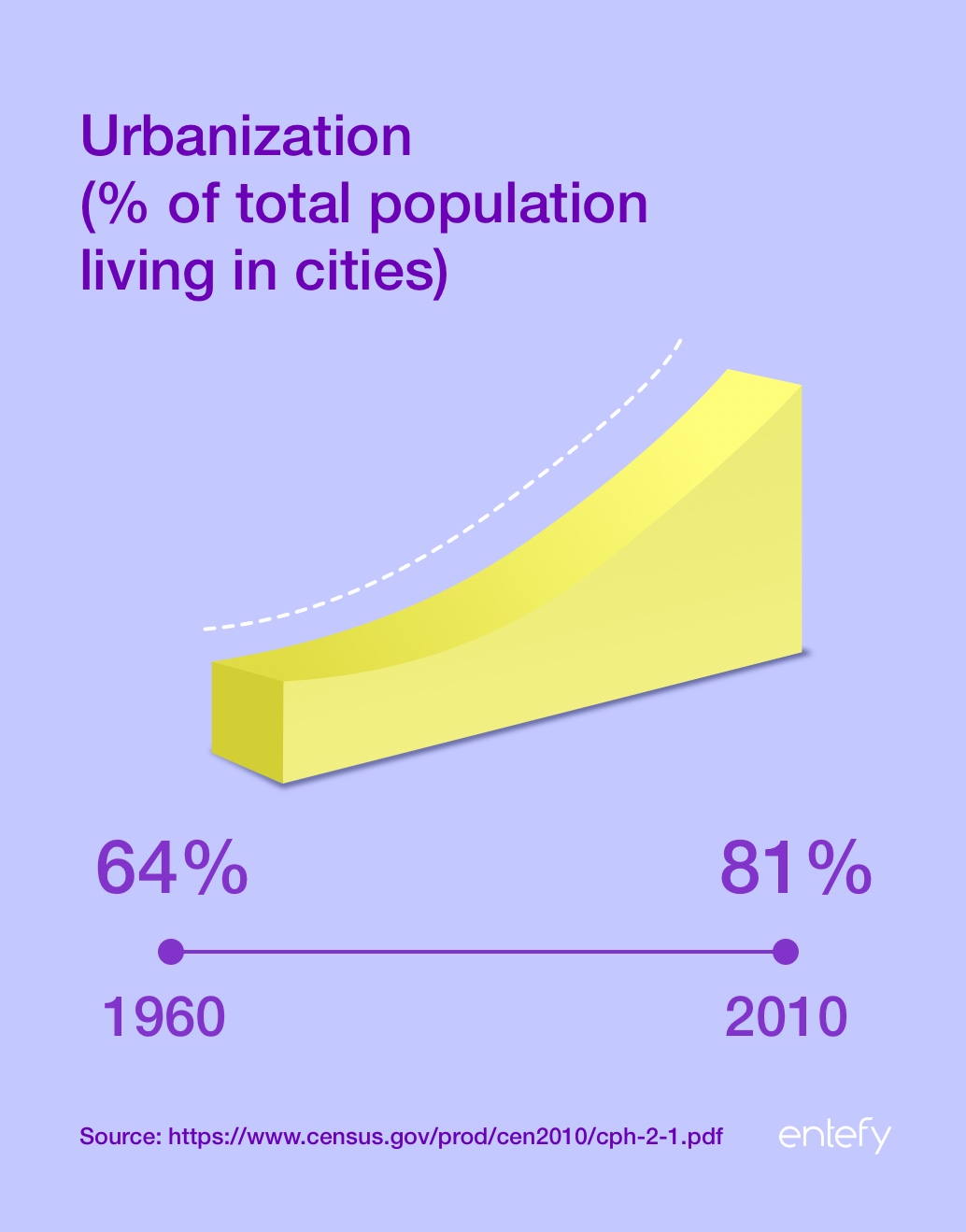

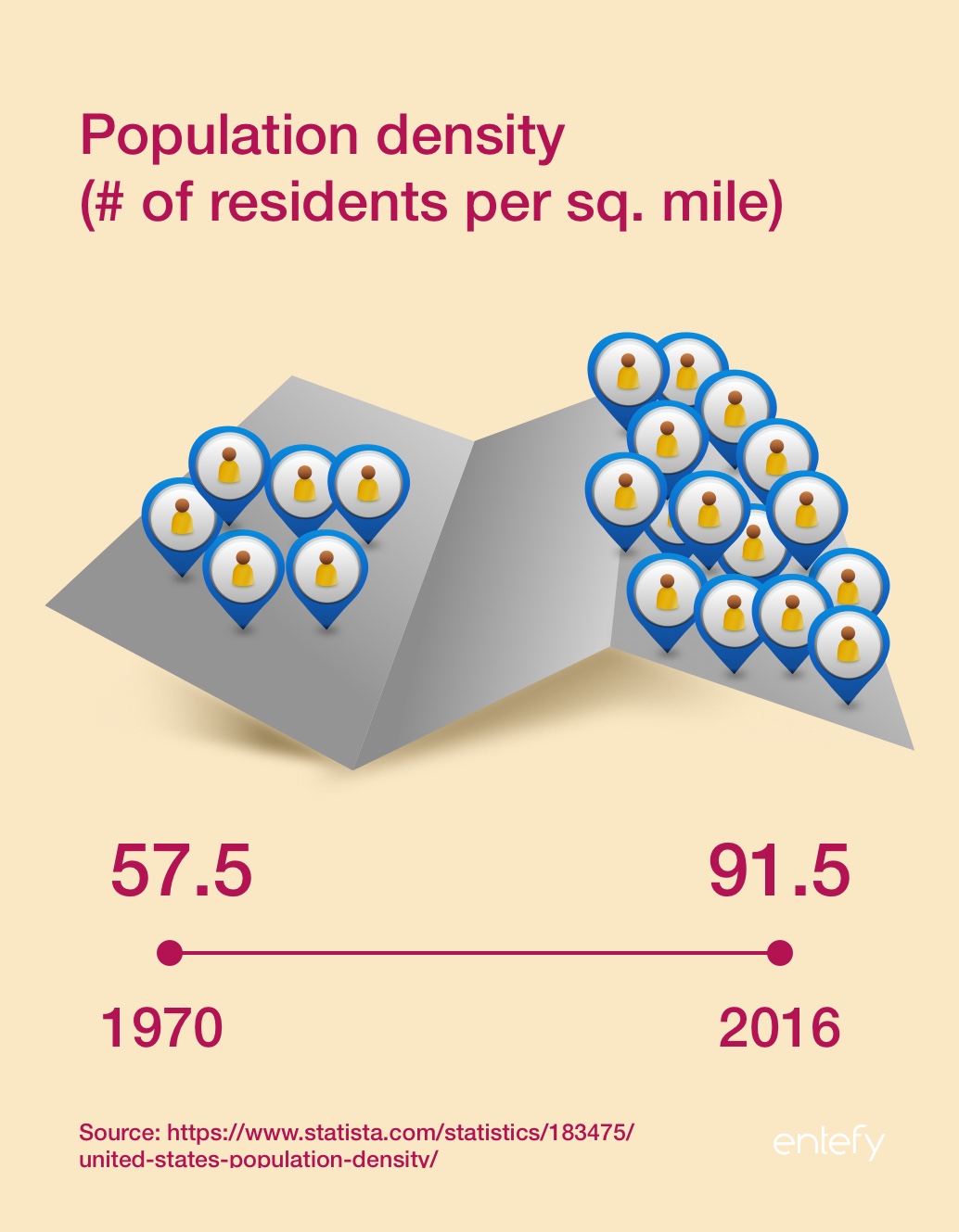

There are other forms of complexity. We are living more densely than we used to do, with nearly half again as many neighbors as we had in 1970. More neighbors mean more interactions but also more chances for contention and conflict.

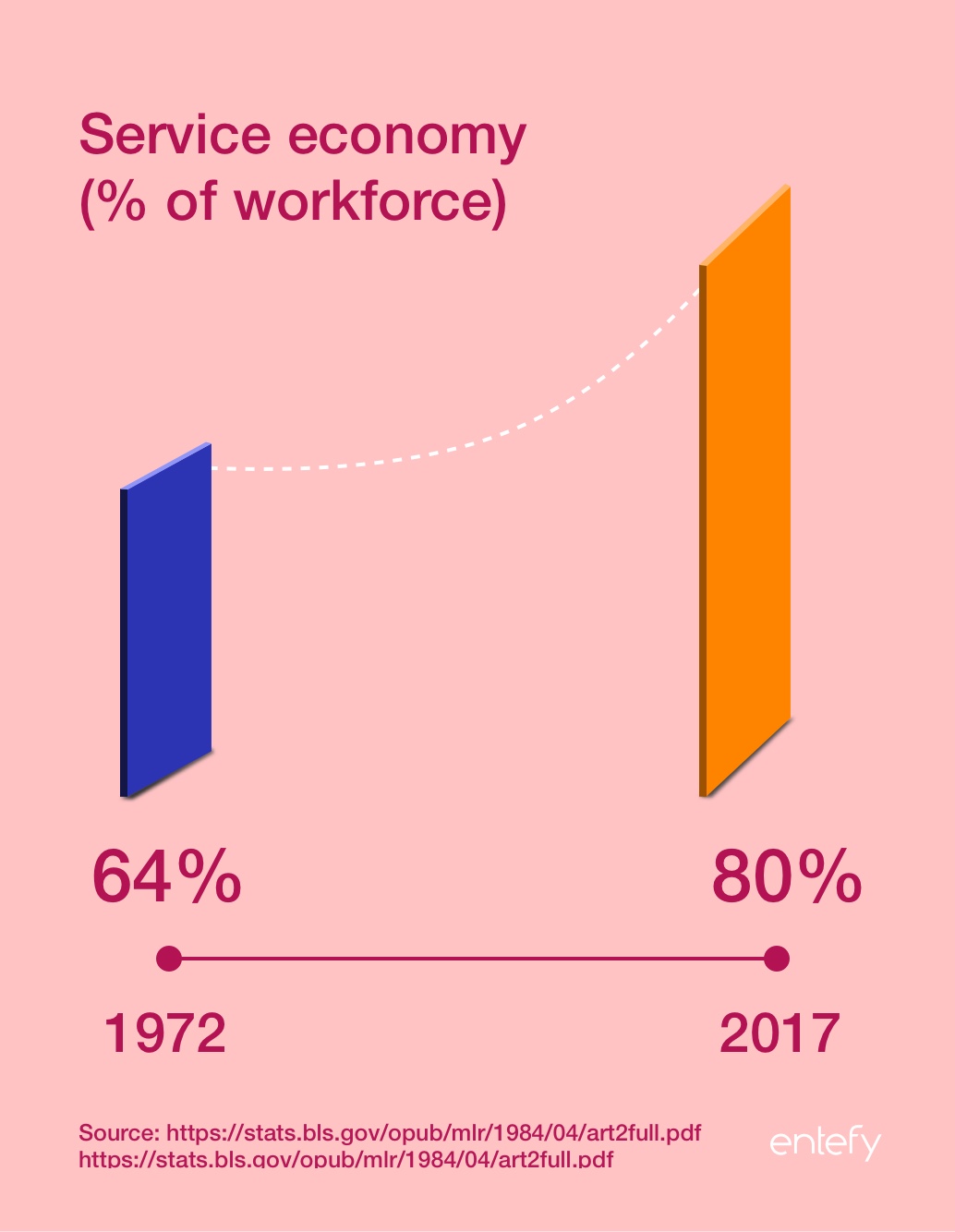

Then there’s employment. In Agriculture, we have been moving off the farm and into cities for more than a century. Manufacturing has seen workers exiting manufacturing jobs for 50 years. Where are these workers headed? Into the Service sector, which is nearly 30% larger today than in 1970—a figure that has a direct link to complexity as well. There is complexity in Agriculture and Manufacturing, but it tends to be slow developing

with long cycle times. The expertise required to drive a tractor or work on an assembly line changes slowly. In contrast, Service sector jobs, roles, processes, and skills tend to evolve quickly. The more that employment is concentrated in the Service sector, the greater uncertainty and volatility there will be for more people.

What is so interesting about complexity is how much the picture of life changes the farther you zoom out from these individual data points. We have become so accustomed to many of the characteristics we discuss here that we take them for granted. Only with some distance can we see what makes the modern world “modern,” and the complexity and consequentiality that define so many of our many decisions.

Part 3 of this report continues Entefy’s analysis of the complexity of modern life with a look at the changes to our confidence in social institutions.