Privacy matters. A quick thought experiment about online and offline privacy shows us why. Let’s say you own a grocery store. And at that store, you have a security camera positioned to record everyone who walks through your door. Customers entering the store understand that the camera is going to record their images and activities while they’re in the store. If a particular customer thinks about this agreement at all, it’s most likely to find it a reasonable exchange of privacy.

With a digital service like a social media app, this privacy exchange is markedly different. Because when an individual installs and uses an app, they are required to agree to what amounts to digital surveillance. The app provider gets to know everything about what users do inside the app; and in many cases actions they take outside of the app. Each user “agreed” to this surveillance via the app maker’s Terms and Conditions and Privacy Policy when they signed up for the service, but often did so by default rather than expressly affirming consent. And since all of the surveillance happens invisibly, the consumer is able to conveniently ignore the data collection and everything that happens to the data after it’s collected.

Now back to the grocery store. For the store to match the same level of surveillance as the social media app we described, its security camera would need to capture not just faces, but names, addresses, birthdays, heights, weights, dietary habits, brand preferences, favorite meals, frequency of cooking at home, conversations about food with friends, and so on. And if simply walking into the store touched off that level of surveillance, a lot of us would be hesitant to walk into the store. Yet billions of people around the world make daily use of digital products that do just that.

The reason that 91% of Americans agree they have lost control of their personal information is because they have. The corporations providing our favorite digital services hold all of the privacy cards. So it’s interesting that in Europe, things are different. One survey found that 31% of respondents felt they had “no control at all” over how their data was used. Why the difference? To understand the state of privacy law in America today, you need to go back to the 1970’s and 1980’s.

At the dawn of the digital age the U.S. established an early lead in enumerating principles and passing laws designed to protect individual data privacy. Those principles would inspire other countries, and the EU in particular, to enact increasingly pro-consumer privacy laws, culminating in the EU’s expansive 2016 General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). GDPR is a unified privacy standard applicable to any company or group collecting and handling personal data about EU citizens.

All is not lost for U.S. privacy policy. Steps could be taken to improve privacy protection and put the U.S. back on the path to leadership in privacy law. But first, the history.

Privacy law at the birth of computing

The U.S. is often criticized by her European counterparts for not having implemented robust and universal data privacy laws.

Yet most people don’t realize that the privacy laws

operating in many countries today are built on foundational principles that emerged from the Fair Information Privacy Practices (FIPPs) framework developed in the U.S. in the 1970’s.

FIPPs defined core digital privacy principles like:

• Notice. A consumer must be told that data has been collected and how it might be used.

• Choice. Defining how data can be used, including the right to opt-in or opt-out.

• Access. A consumer’s right to see data about themselves and verify or contest its accuracy.

FIPPs emerged in the 1973 U.S. Advisory Committee Report on Automated Data Systems. The report was prepared by the Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare in response to the first major computer systems containing what today we would call personally identifiable data. The Forward to the report begins with a surprisingly prescient pronouncement: “Computers linked together through high-speed telecommunications networks are destined to become the principal medium for making, storing, and using records about people.”

The report goes on to propose fundamental principles for designing and regulating computer systems that record, store, and protect data about one or more aspects of the life of a specific person. This was a major milestone for digital privacy. The language in the report remains highly relevant today:

“An individual’s personal privacy is directly affected by the kind of disclosure and use made of identifiable information about him in a record. A record containing information about an individual in identifiable form must, therefore, be governed by procedures that afford the individual a right to participate in deciding what the content of the record will be, and what disclosure and use will be made of the identifiable information in it. Any recording, disclosure, and use of identifiable personal information not governed by such procedures must be proscribed as an unfair information practice unless such recording, disclosure or use is specifically authorized by law.”

In plain language, this passage translates into something like: “If I say you can make a record about me, you agree that I’ll know exactly what is recorded and how it will be used; and I’ll have the right to correct or delete it if it’s wrong. Any behavior outside of these limits is illegal.” This was FIPPs in a nutshell.

In the 1980’s, FIPPs went international. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) embedded FIPPs in its privacy guidelines. The OECD is an intergovernmental economic organization with 35 member countries, including most of the world’s largest economies. The OECD published data privacy guidelines to which its members agreed to voluntarily adhere. Again, the language of this agreement seems fresh and relevant today. The OECD guidelines recognized:

“That, although national laws and policies may differ, Member countries have a common interest in protecting privacy and individual liberties, and in reconciling fundamental but competing values such as privacy and the free flow of information.”

It was already clear that a natural tension existed between an individual’s right to privacy and a corporation’s desire to profit from that individual giving up some of that privacy.

Back in Europe, FIPPs was at the heart of the Council of Europe’s “Convention 108” treaty in 1981. The Council of Europe is the continent’s leading human rights organization. Its membership is larger than the more exclusive EU, and its primary purpose is promoting human rights. Emphasis on “rights.” Because here we see FIPPs graduate from what had been principles in the U.S. to what became a right in Europe. Again, the language is relevant today:

“This Convention is the first binding international instrument which protects the individual against abuses which may accompany the collection and processing of personal data and which seeks to regulate at the same time the transfrontier flow of personal data. In addition to providing guarantees in relation to the collection and processing of personal data, it outlaws the processing of ‘sensitive’ data on a person’s race, politics, health, religion, sexual life, criminal record, etc., in the absence of proper legal safeguards. The Convention also enshrines the individual’s right to know that information is stored on him or her and, if necessary, to have it corrected.”

On the path to the right to privacy

Since the Internet era began in the 1990’s, the U.S. has taken a back seat to the EU in the continuing development of privacy laws.

By the mid-1990’s, the EU sought to address inconsistent enforcement of the Convention 108 treaty by passing the EU Data Protection Directive in 1995. This was a major step toward achieving EU-wide uniformity in every sector of society. Here we see clearly that privacy is firmly enshrined as a right. Article 1 of the law defined the importance of individual privacy succinctly: “Member States shall protect the fundamental rights and freedoms of natural persons, and in particular their right to privacy with respect to the processing of personal data.”

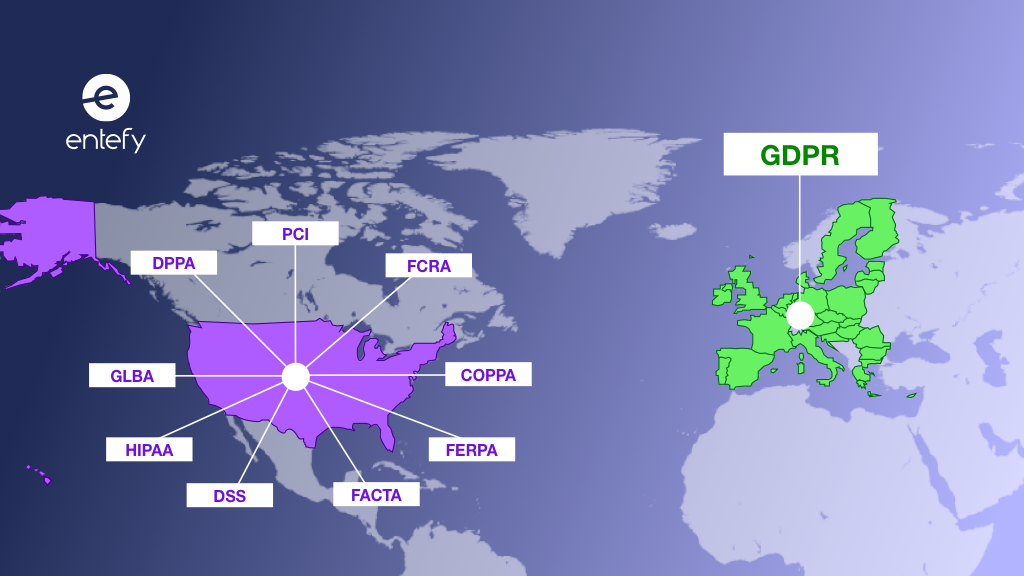

To understand just how differently privacy was treated in the EU and the U.S. at this time, we need only ask what was happening in the U.S. in 1995. Rather than attempt a comprehensive privacy approach, the U.S. was creating narrow, sector-specific privacy laws covering, for example, our health records, our children, our driving records, and our financial records. We recognized that certain parts of our lives deserved special privacy protection mandated by the government but we stopped short of applying the same principles to other parts of our lives. And, importantly, we left the rest of our privately identifiable information as fair game. But why?

It’s an important question, and one the EU answered with the General Data Protection Regulation, the granddaddy of consumer-friendly privacy laws. The European Commission approved GDPR in April 2016 and it is expected to be enacted by May 2018. GDPR is Europe’s attempt to harmonize data protection regulations and even attempts to extend EU privacy principles to any company doing business with EU citizens.

FIPPs, and the U.S.’ lead in digital privacy law, is today a footnote to a footnote.

What the U.S. can do to protect its citizens

Today, more than 100 data protection laws exist worldwide. And all of those laws have a common set of core principles which consist of: notice to consumers; transparency towards individuals regarding how their information will be used; choice for the individual, furnishing them the opportunity to give consent or to object to how their data is being used; access to their data, for example, to correct the information should it be out of date; and security of their data.

The problem isn’t that the U.S. lacks any privacy regulation. In fact, there are laws like the Fair Credit Reporting Act of 1970 (FCRA), the Driver’s Privacy Protection Act of 1994 (DPPA), the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA), and the Children’s Online Privacy Protection Act of 1998 (COPPA). And, in addition, most states have enacted some form of privacy legislation. The problem is that U.S. laws only provide some protection for some of our personal identifiable information, not comprehensive protection for all of our data.

But there are two significant omissions in privacy protection in the U.S. today: universal protection for the core privacy principles once enshrined in FIPPs; and the fundamental recognition to a right to privacy. To regain its leadership in privacy rights, the U.S. could:

1. Expand privacy as a right for all personal identifiable information, not just for some.

2. Ensure that before any data collection, consumers are clearly and simply informed of exactly what personal data will be collected prior to opting in.

3. Prohibit data collectors from selling personal data collected without express permission of the consumer.

In today’s global business environment, GDPR’s relevance to companies doing business in Europe means that practically every U.S. multinational will be required to abide by that law. Formal adoption of a universal, comprehensive, consumer-friendly privacy law could benefit American consumers and businesses alike. There is still much history to be written.