Will an AI system ever create art that can equal a work created by a human? Researchers and artists are already making attempts to find out by translating creativity into algorithms. To answer whether these attempts are likely to generate artwork—music, poetry, fiction, visual art—that can pass for human-created work starts with understanding how human creativity functions.

While the potential for rational thinking and mathematical ability in humans are present at birth, we still require education to fully realize these capabilities. So we study the laws of nature, logic puzzles, ethical dilemmas, and so on. Yet even the best of us make the odd irrational decision and give in to one of our many biases.

On the other hand, human emotion, intuition, and creativity needs little formal training. Every child will laugh, cry, draw, create, destroy, question, and explore without any prompting, let alone education. Education is used to shape these urges, teaching children to take control of their emotions, direct their creativity, and destroy or create with more precision and consideration.

Computer systems are something quite different. They excel at algorithmic tasks yet lack most capabilities that we consider innately human. They can certainly calculate in milliseconds tasks too complex for a roomful of mathematicians, but just try telling a computer a joke or playing it a love song.

Even at the rapid rate at which advances are happening in artificial intelligence, it’s an open question whether an AI system can learn to create something that a human would consider art. Yet advances in areas not directly related to creativity suggest it might happen. Algorithms are already completing some of the most difficult logic puzzles humans have devised. AI systems are taking on the challenge of understanding language, others have beaten the best human players in games like Go and chess, and now they are taking to the streets to prove how much safer they are as drivers.

Many of these skills are only a short distance away from creativity itself. Language, in particular, follows prescribed organizational rules while also allowing space for artistic pursuits like storytelling and poetry. Yet while we might call music “organized sound,” and visual art to be “organized color,” any old organization won’t do for an AI-generated artwork to achieve that most timeless of standards: Art with a capital “A.”

The mechanics of human creativity

It is fascinating that the human brain is wired for both logic and creativity, given how fundamentally different those mental processes are. Logic runs on a set of rules and procedures in an orderly fashion. Creativity and intuition, on the other hand, can be messy, anything but straightforward.

First, we should acknowledge that there are at least two forms of creativity. We might call the inspirational thought that arrives in the shower an example of “a-ha” creativity. Then there’s creativity that flows while we’re “in the zone,” letting our mind stretch and test rules and norms, like a pianist does when improvising a solo. In both of these circumstances, focus and cognition stand aside to let emotional expression and subconscious freedom take charge.

Mind wandering, that mental state of relinquishing conscious thought to let the mind go where it so chooses, has been linked to creative processes on more than one occasion. Insights emerge from mind wandering as the images and ideas flowing through it strike upon something rich and unexpected. Unlike a mathematical formula or logical construction, these processes are not easily recreated in computer form.

Long before formal psychological research into creativity, artists had caught on to the power of mind-wandering. The Surrealist painter Salvador Dali used to hold keys in his hand above a plate as he sat in his chair, aware that in those blissful moments just before sleep, when strange thoughts would creep in, the keys would drop, wake him, and leave him with those ideas of which he could then use.

Not every shower thought is worthy of being called creative. Some ideas seem ridiculous the next day, some musical transitions are just plain jarring. For creativity to attain Art status takes something far subtler. Creators must know the rules before they can break them effectively, they must have a sense of what will work to create the feeling, sensation, or effect that they seek. In this way, they are, to an extent, introducing old ideas to new ideas. Artists combine things in new ways, look at them from a fresh perspective, but do so using materials (colors, phrases, melodies) we are already familiar with.

This supports the common notion, so succinctly put into words by Steve Jobs, that “creativity is just connecting things.” Though the “just” makes it seem far easier than it actually is. We cannot connect just anything haphazardly and label it creative. It needs a purpose, a point, whether that is to solve a problem or portray an idea. We can teach AI systems to mix things together (imagery, tones, words), but can we get them to do so in a meaningful, artful way?

Attempts at artificial creativity

The extreme challenge of not only figuring out how creativity works but teaching it to an intelligent machine has not stopped researchers from trying. There are numerous examples of AI systems that can compose music, write articles, and create visual art. And some of it is difficult to distinguish from human-made art.

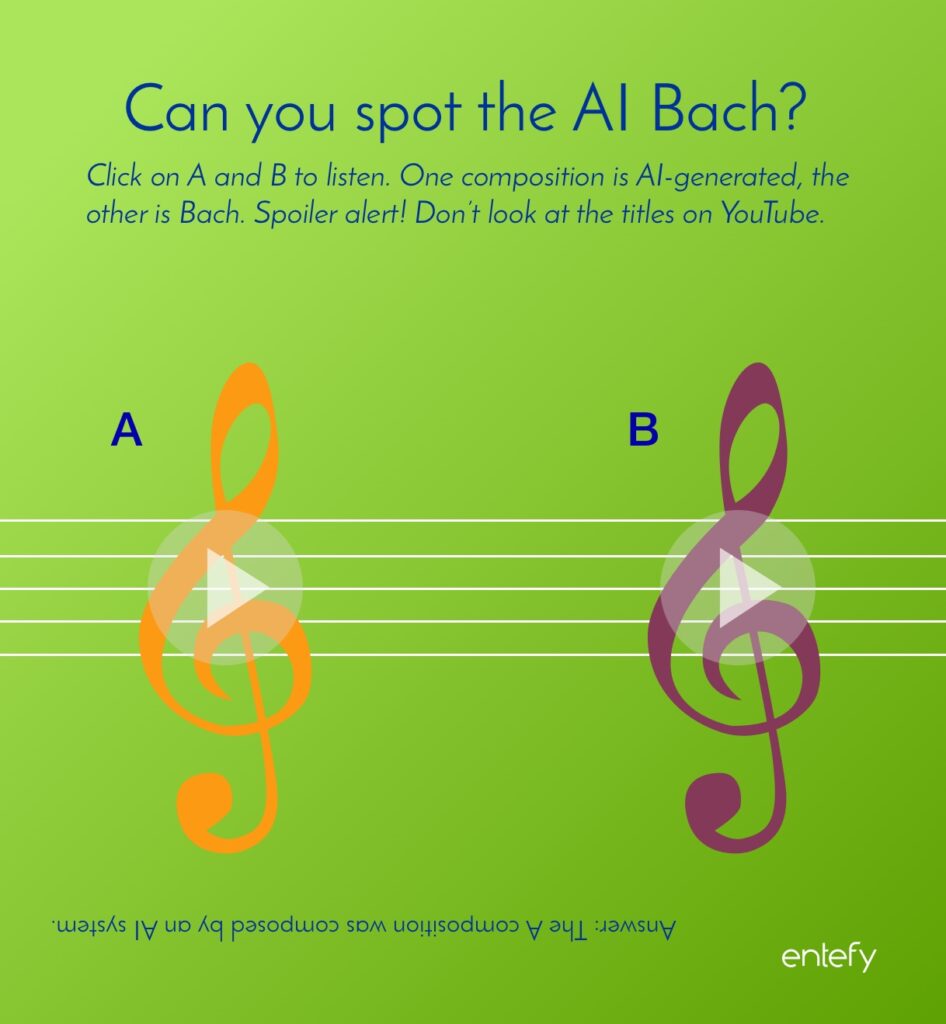

Gaetan Hadjeres and Francois Pachet, from the Sony Computer Science Laboratories in Paris, trained their AI system on the chorale cantata music of Johann Sebastian Bach. These compositions were chosen, as MIT Tech Review notes, “because the process of producing them is step-like and algorithmic.” The AI system was trained using 352 of Bach’s chorales, which were transposed into different keys, for a total of 2,503 compositions. When it came to producing its own Bach-infused chorale, the AI system managed to convince more than half of 1,600 listeners—including professional musicians and music students—that the harmonies were from Bach himself.

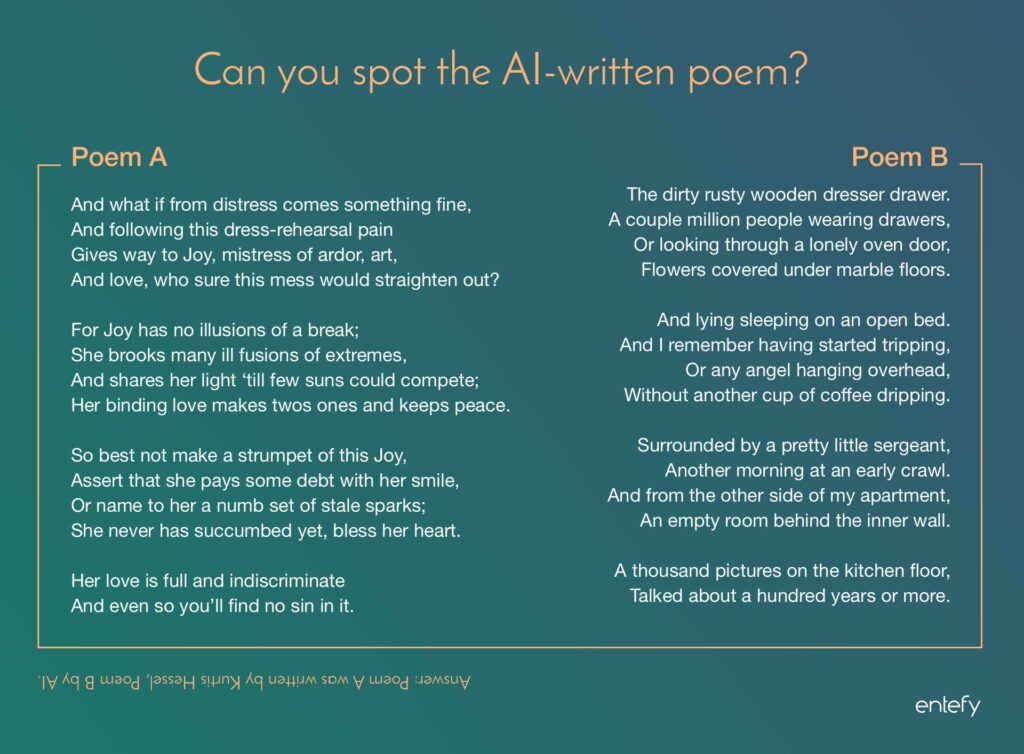

Bach doesn’t appear to challenge AI as much as poetry does. In a competition run by Dartmouth, judges were tasked with reading 10 sonnets, fourteen line poems with prescribed rhyming schemes. Some were written by a human, others by a machine. In this case, all of the judges were able to recognize the artificial compositions.

What about attempts at AI-generated fiction? One machine learning enthusiast shared an introduction to setting up a deep writing neural network in a post on Medium. He used the methodology to train a deep learning algorithm on the first four books of the Harry Potter series and shared the results. While the AI-generated fiction is an entertaining read, J.K. Rowling hardly needs to worry:

“The Malfoys!” said Hermione.

Harry was watching him. He looked like Madame Maxime. When she strode up the wrong staircase to visit himself.

“I’m afraid I’ve definitely been suspended from power, no chance — indeed?” said Snape. He put his head back behind them and read groups as they crossed a corner and fluttered down onto their ink lamp, and picked up his spoon. The doorbell rang. It was a lot cleaner down in London.

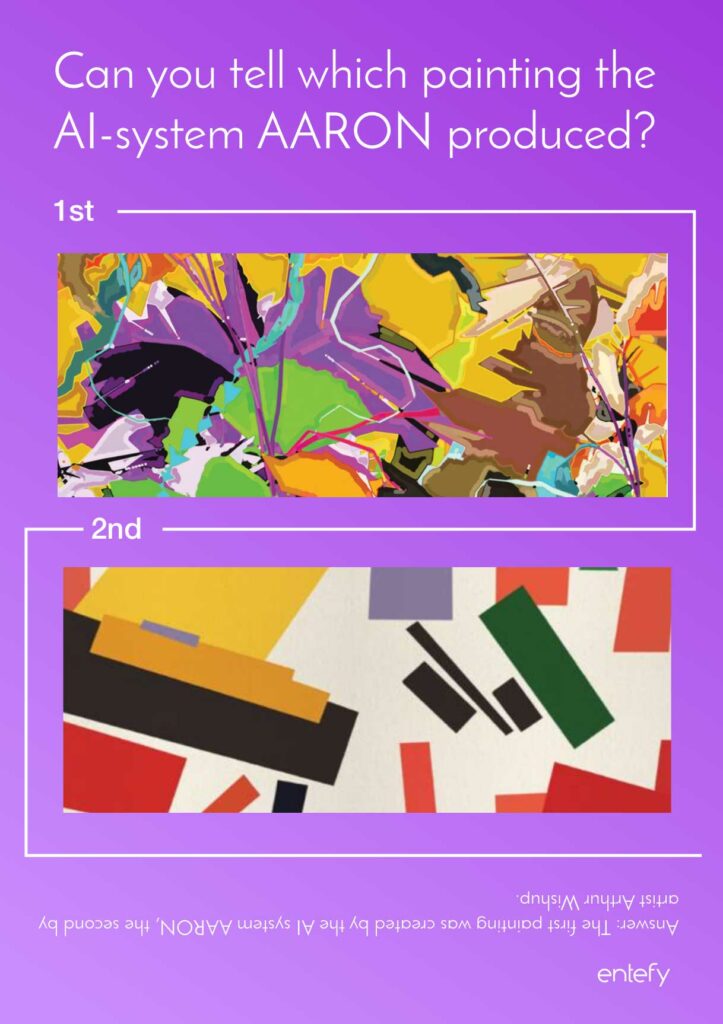

In the visual arts, AARON has been around for some time. The child of artist Harold Cohen, AARON was born in 1973 as Cohen became increasingly interested in computers and the potential they had to paint for themselves.

In a BBC interview about intelligent machines, Cohen stated that AARON had “become autonomous enough to disturb the guy who wrote the program.” Yet Cohen denied that AARON was truly creative, believing that the system’s true creativity was many years away: “I don’t deny the possibility that, at some point in the future, a machine can make something approaching art – but it is going to be a lot more complex than teaching a car to drive around a city without a driver, and it isn’t going to happen next Wednesday or even in what is left of this century.” In the years since AARON’s creation, the system has produced many vibrant-colored abstract paintings.

Appreciating machine-made art

One important question remains. How are we going to feel about Art produced by intelligent machines? Will we appreciate the creativity and design? Or will it seem cold and distant, denying us an emotional connection to it?

One school of thought says that the value and meaning of art exist independent of its creator. On the other hand, many believe that the story behind a piece of art and information about the artist can influence our perception of the artwork. You can test your own view with a thought experiment: Imagine standing in front of a painting by a noteworthy artist. Now imagine learning that the painting was a forgery, a copy of the original. Would you still find enjoyment in it? If every brush stroke, hue, and detail were precisely the same, would you value it the same?

Psychologist Paul Bloom notes in an interview on what people value most that when we’re shown an object or a person’s face, “people’s assessment of it…is deeply affected by what you tell them about it.” This idea was demonstrated in an experiment in which a violinist plays a piece of music in a D.C. Metro station and collects $32 in donations. What passersby were not told was that the violinist was Joshua Bell, who has recorded more than 30 albums and performed at the White House. Bell was playing a Bach composition considered one of the most challenging ever written. Just days earlier, Bell had played the piece in Boston’s Symphony Hall, where ticket prices eclipsed $100. Would more people have stopped to listen to him play if they had known all of this? Almost certainly. Yet the music would have been the same.

Creativity will remain a human domain for some time to come

As it stands today, creativity remains a human affair. While these AI attempts are noble in their artistic pursuits, each still falls short of the benchmark set by artists of our own kind. The musical compositions were the most convincing artifacts, yet were chosen specifically for their algorithmic style. In most other domains, the algorithms displayed an inability to break the rules in a purposeful fashion, often sticking to the norms or composing something incoherent. No one knows when a digital Picasso might emerge to wow an audience of Art-world cognoscenti. But one thing is for certain, as machines become smarter and more capable, they get closer and closer to achieving true creativity.