There is one small problem with digital advertisements: people hate seeing them everywhere. Like cigarette butts in parks, ads pollute digital environments by ruining your experience and distracting your focus. Every day that passes brings more ads in more places, a trend that shows no signs of changing.

But it could change if advertisers were to think more creatively about how to engage with their customers and consumers were to more actively exercise their power of choice. Both start with understanding why companies continue to invest heavily in digital advertising despite low success rates and high levels of consumer annoyance.

Because ads-everywhere-you-look isn’t inevitable. The Internet has evolved multiple channels for consumers to learn about products and services, and engage directly with companies. Brand-sponsored content is very effective at explaining how products work and how they can fit into your life. Online forums and communities provide outlets for consumers to ask questions from users of a particular product. Robust customer review systems prioritize the display of quality, relevant reviews (both positive and negative) by verified owners.

The problem with many of these ad alternatives is that they exist outside of the advertiser’s control; they are user-led and user-generated. The fact that many consumers prefer these alternatives is something many companies choose to ignore. Ads have been around forever, they’re safe, and anything that isn’t advertising seems risky. This is, quite simply, a lack of imagination. And consumers suffer for it.

The intrusive, distracting, annoying price of convenience

The public’s disdain for ads is true in TV, radio, print, and especially online, where one survey showed 64% of people find ads “annoying and intrusive.” Why TiVo? Because you can skip the TV ads. What is one of the keys to SiriusXM’s success? No radio ads. Why are newspapers and magazines being forced to reinvent themselves? People aren’t reading the ads so the advertisers are abandoning the format. And what about the web? AdBlock Plus, the top ad blocker software on desktops and mobile devices, has been downloaded more than 1 billion times.

Yet we’re told that ads are the “price of convenience.” When apps and services are offered for free, we accept that ads are how we pay for the software. There is a certain fairness to that—but only up to a point. Because free apps don’t merely show us an ad or two when we use them. Our activities inside the app, and even the things we do on our devices when we’re not in the app, are tracked, collected, bundled, and resold to third parties. The ads we see are one small part of a complex advertising ecosystem in which more than 2,500 different companies are battling to monetize our behavior. The price of “free” is far, far higher than the occasional banner ad.

Targeted ads aren’t that bad…oh, wait, yes they are

It’s startling to contrast just how much digital ads there are with just how ineffective they can be. By one estimate, the average person is exposed to 362 ads per day counting digital and offline channels. One widely cited figure of 5,000 ad exposures per day turns out to be a myth. Looking at it from a purely digital angle, Google acknowledged that 56.1% of its ad impressions were not viewed. About 60% of clicks on mobile banner ads are accidents. And only 0.13% of display ads actually attract a click.

Despite this dismal effectiveness, U.S. advertisers are on track to spend more online than on television for the first time ever. The thinking is that digital user-tracking technologies have matured to the point where an advertiser can insert itself and its message practically anywhere, at any time. And target very narrow groups of potential customers.

On the surface, targeted advertising doesn’t sound like such a bad thing (“If I’m going to see a bunch of ads all the time, they might as well be relevant to me”). But here’s the problem with that: relevance is tied to the use of personal data. If you have ever noticed an ad on the margin of a web page advertising something very specific that could only be there because of an email you sent or a search you made, then you know this is at best an icky feeling (“I guess it’s all just algorithms and no one actually read that email”) and at worst an outrage (“When did I agree to let anyone read my private correspondence, algorithm or not!?”).

Advertisers compound the problem, and publishers love that

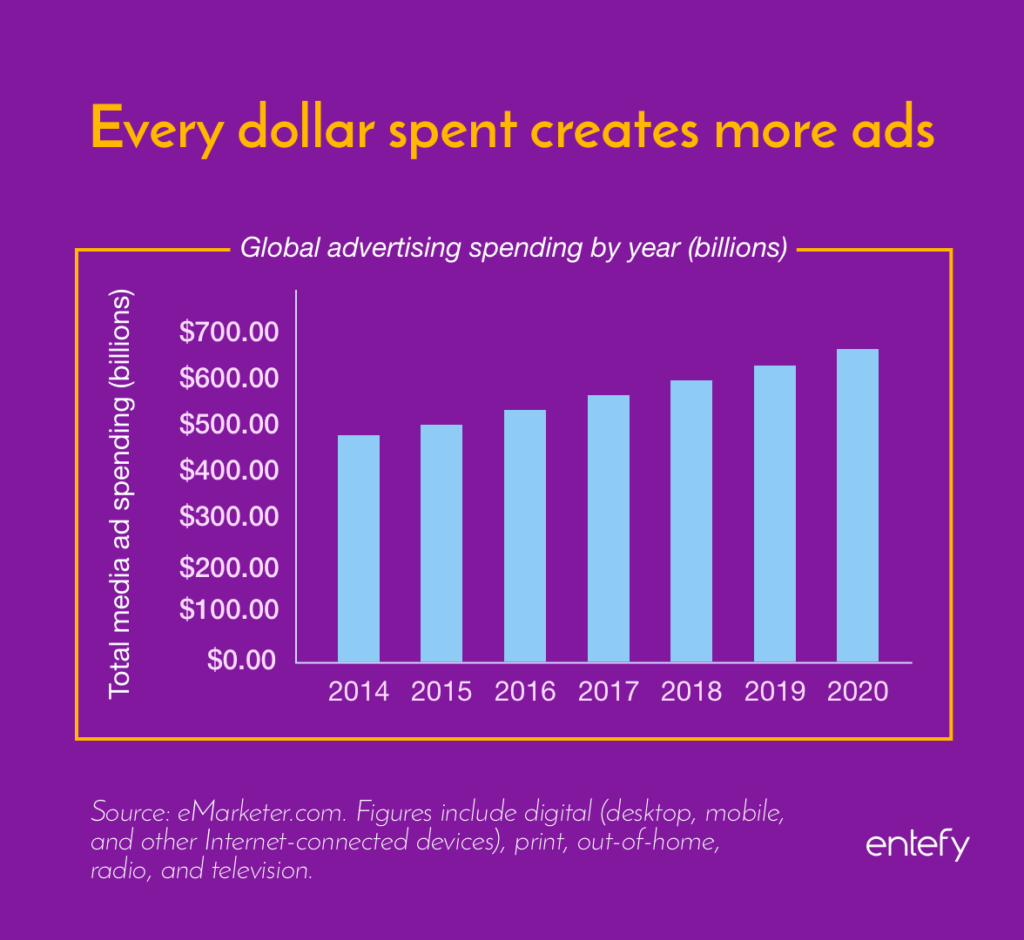

If there’s so much negative sentiment towards ads, why do advertisers bother? Because if they do enough advertising, that dismal sub-1% response rate can add up. Let’s say a company buys 100,000 ad placements in a month, and those ads generate $1 million in revenue. During the next period, however, consumers are less responsive and the same level of ad spending leads to just $500,000 in sales. Because there is no easy way to make consumers respond to its ads, the company decides to double its ad placements. They purchase 200,000 ad placements to bring sales back to $1 million. But six months later, sales are down by half again. What next? Double the ads. 400,000… 800,000… 1,600,000… 3,200,000… and soon, you get to a lot of ads. But just how many?

The precise answer to this question is difficult to ascertain, but what’s easier to measure is the dollars spent. Annually, global advertising spending has reached $600 billion, $235 billion of which is dedicated to digital and mobile advertising alone.

Advertisers buy more ads, people ignore the ads or adopt ad blockers, and in response advertisers serve up trillions of ads every year. If you’re someone that objects to all of this digital clutter, what’s to be done?

Empowered consumers can break the cycle

Quality is rarely free. If the price of “free”—data trackers, privacy violations, digital pollution—doesn’t sit well with you, then you need to get selective. There are two digital environments covered in ads where you have ad-free alternatives: content and apps.

On the content side, accept that subscriptions are how publishers keep the lights on. You can support the writers and publications that you value through subscriptions. Publishers have a responsibility for keeping those subscription prices affordable. Technologies like micropayments create consumer-friendly alternatives to the standard annual subscription.

On the software side, make the app explosion work for you. With approximately 4 million apps available in the app stores, there are usually several high-quality options for any given software category. Be sure to carefully read Terms of Service to verify that data tracking and monetization activities that you find objectionable are not employed by the developer. Be very discerning when using app services that track your behavior across multiple apps—these platforms are generally where the most egregious personal data collection and monetization take place.

Many software companies offer free versions of their apps for basic users, and paid versions for power users in which additional features are enabled. This so-called freemium business model links a software company’s financial success to the quality and usability of its product. It aligns their incentives with your own.

If advertisers and publishers could, every website, every newspaper, every TV channel, every radio station, and every surface in every public space would be covered with advertising. There are, after all, already ads on the floors of supermarkets, ads flown by drones, and ads inside urinals.

If we don’t become accustomed to paying for quality, the future is more personal data monetization and more ads. But there is a bright, shiny, clutter-free future in which our digital environments contain fewer and fewer ads. It takes informed consumers making informed decisions to get us there.