Entefy’s research into the complexity of modern life concludes below. In Part 1: The bygone Golden Age, we outline the paradox of prosperity, the observation that despite widespread evidence of the world’s progress, our individual experience of life is often something quite different. In Part 2: Defining modern complexity, we analyze the aspects of life today that create the experience of complexity and consequentiality. In Part 3: The general erosion of confidence, we look at the evolution of our collective trust in social institutions. In Part 4: Family, friends, and community, we analyze the structure of social circles and changes to income and education. The report concludes by examining how digital technologies can contribute to meaning and fulfillment in modern life.

Part 4: Family, friends, and community

Picture two friends. They share similar tastes and preferences, world views, and life experiences. Individually, each one shares similar bonds with other people, friends, family, colleagues, and so on. And each of those persons has their own bonds. These bonds extend outward to include practically everyone in the world. Each person is unique, but when the shared viewpoints are extended outwards far enough, you have what we call society.

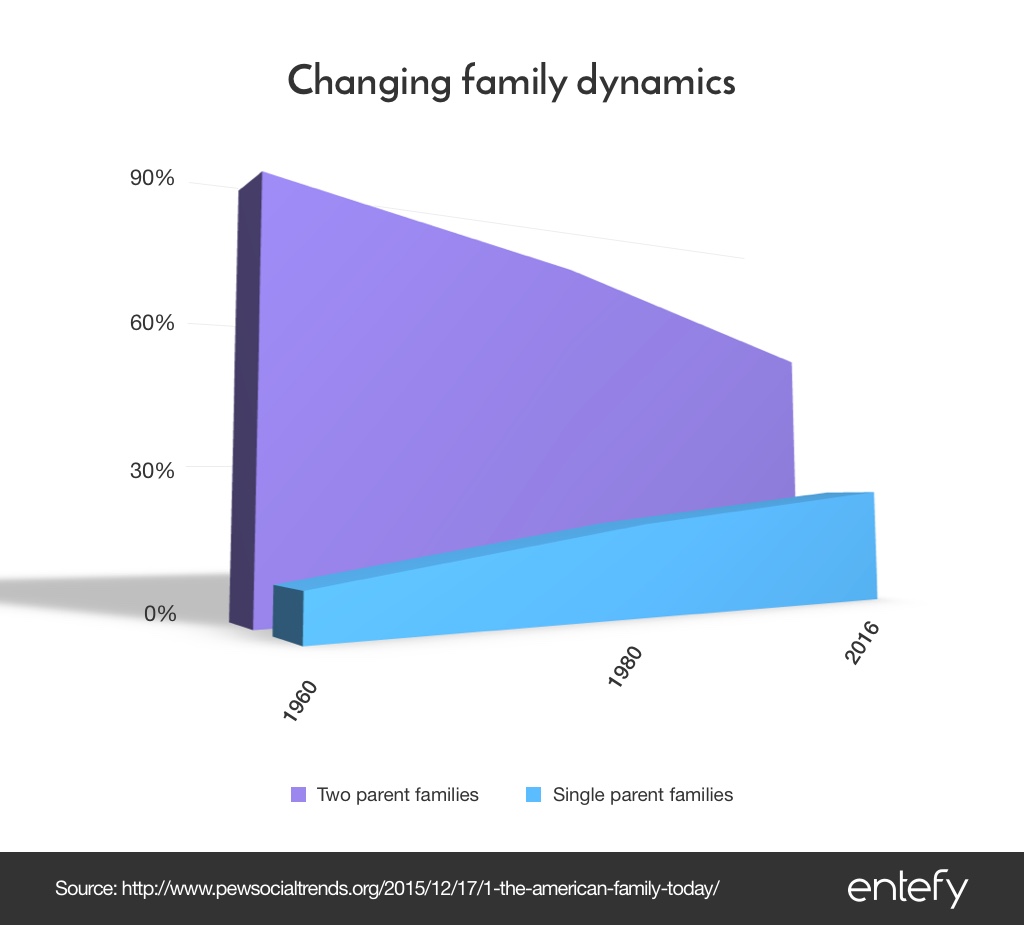

Today, after nearly 50 years of rapid social evolution, the U.S. has far more variety, diversity, and complexity than ever before. Here is another face of the complexity we’ve been describing: the changes to traditional family structures, friend networks, and communities. The rise of single parenthood and the decline of the middle class are two aspects of these changes.

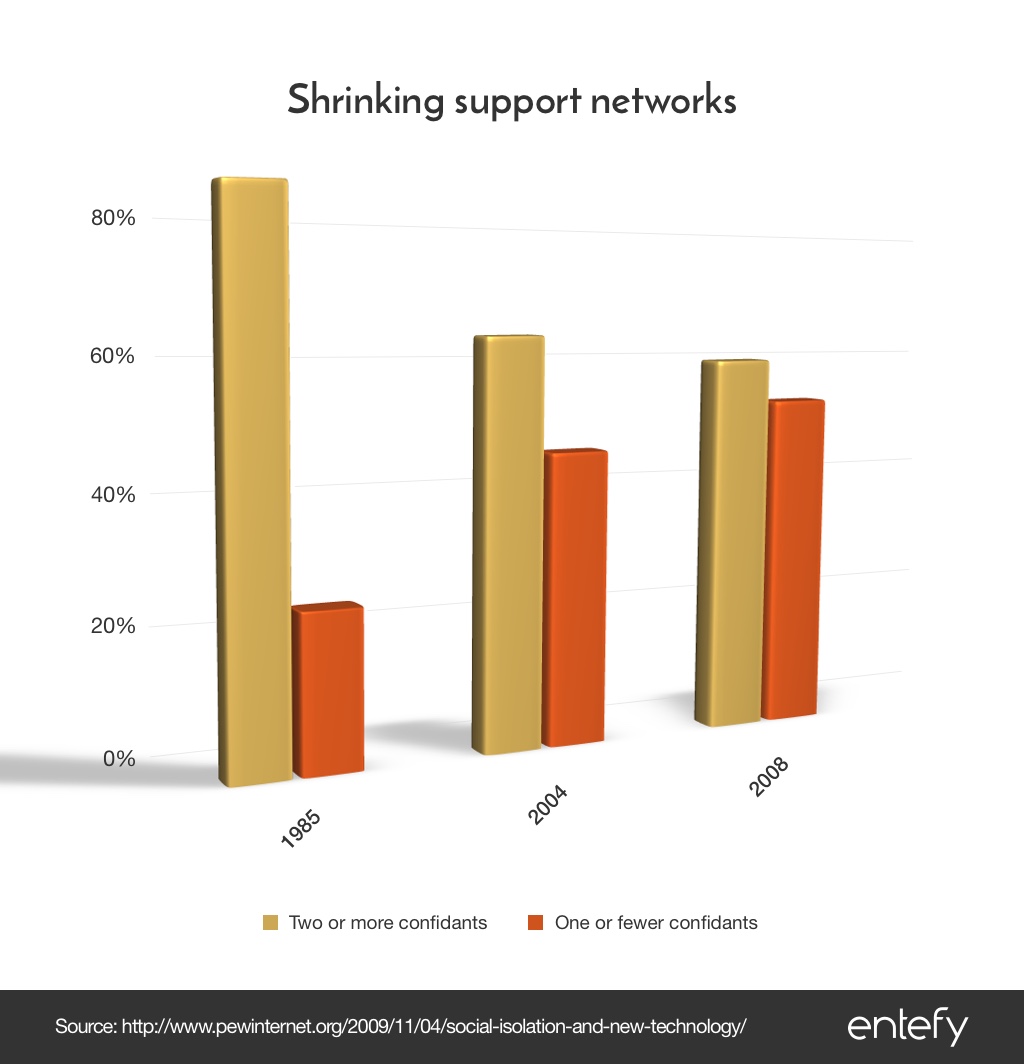

The U.S. in the 1960’s had more elements of a consistency in family and friend structure. For example, 87% of families included two parents, according to Pew Research Center. However, by 2014 that figure had declined to 61%. Similarly, in 1985 78% of survey participants indicated having more than 1 friend. Whereas today, that figure is much lower at only 53%.

The number of households with only a single person has risen from 13% in 1960 to 28% in 2016. The number of people with many friends is small (15%) and is down 72% from where it was in 1985. While post-Internet communication technologies created the capacity for broad virtual relationships, the data nonetheless describes a very different story of personal connection, or lack of it. When you factor in that labor force participation is declining, more and more people are essentially disengaged, not just from friends and family but from meaningful interaction with others.

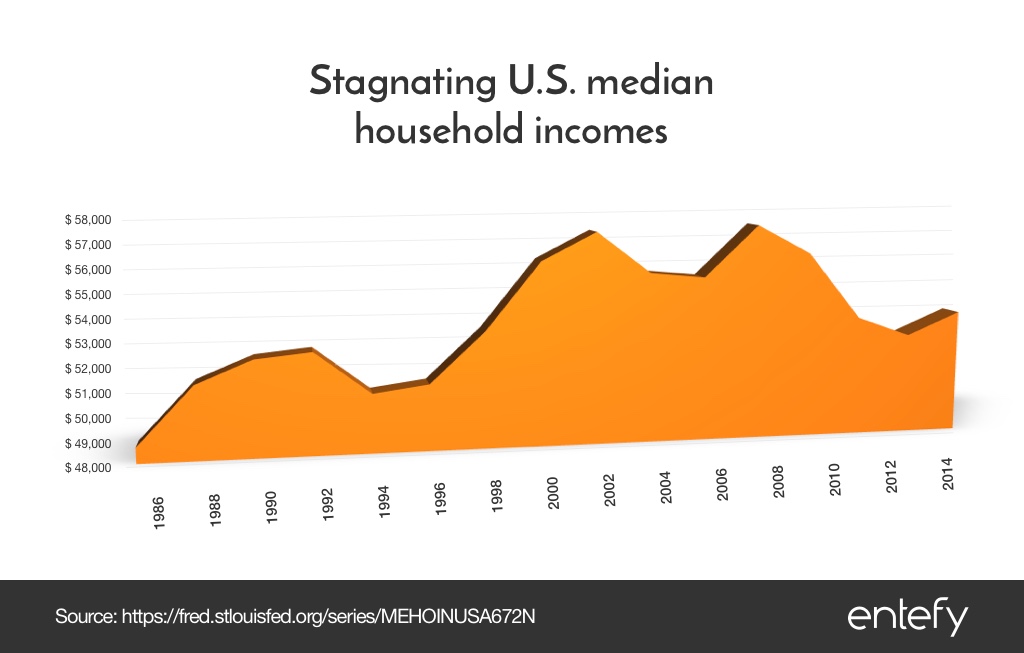

Next is money. While U.S. real median household income is high by global standards, it has also been relatively stagnant for the past twenty years. Importantly, this stagnation comes after fully 50 years of steady increases. The reliability of these income increases and the fact that they were spread quite widely across social tiers was a major factor underpinning the “American Dream” itself.

The importance of increasing income is not solely monetary. Higher income creates options for the wage earner and helps buffer households from unexpected shocks and setbacks. In contrast today, a static income, even a high one, represents a decline in expectations alongside the practical reduction in capacity to address unexpected setbacks.

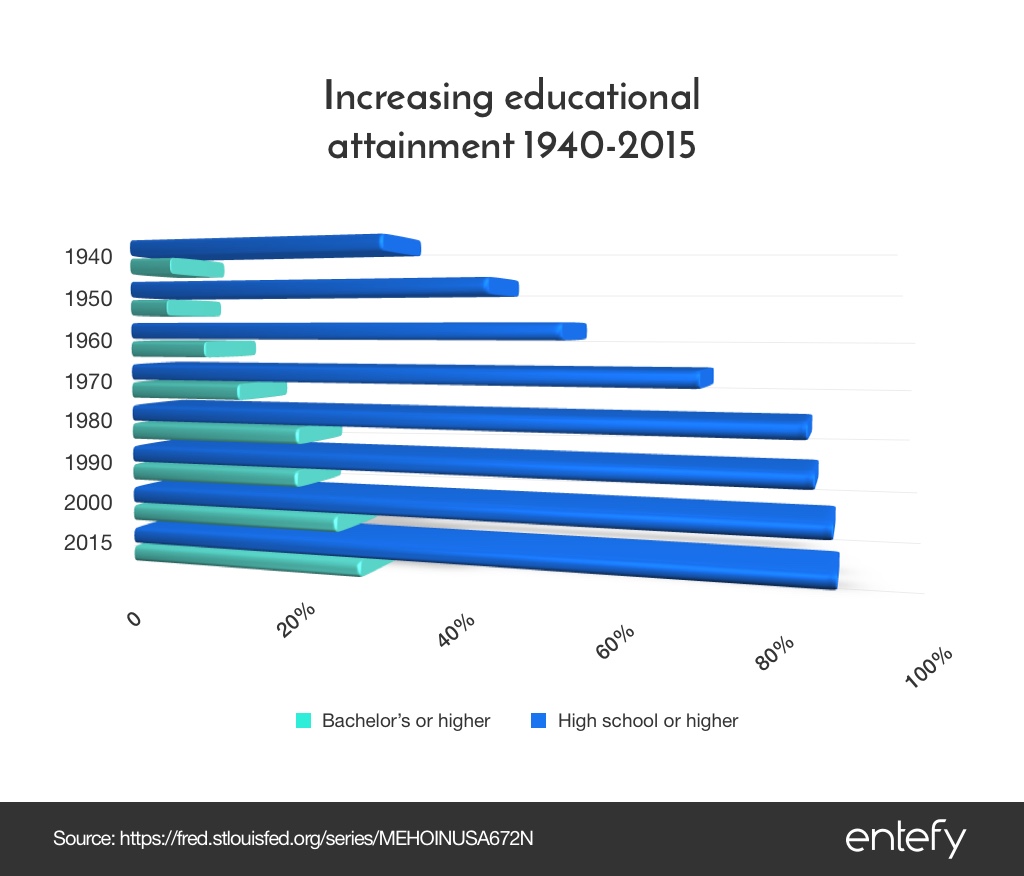

There are complex aspects to educational attainment as well. The percent of the population with a college degree has been rising steadily since 1940. That figure is higher than ever today at 32.5%. While a more educated workforce is a good thing from a societal perspective, from an individual perspective, that simply means more competition. When 5% of the population had a college degree, that represented a near-guarantee of high-paying, opportunity-filled work. At 32.5%, the degree represents a less valuable credential and less of a guarantee for future prosperity.

As we saw with the general erosion of confidence in social institutions, the true impact of these changes is best understood with some distance. Single data points do not tell the whole story. Taken together, rapid changes to the nature of our connections to friends and families have created for many people a sense of…something. Nostalgia for a better yesterday. Confusion and distrust towards today. Or in some cases the widespread anger that propelled an outsider to the Presidency in the 2016 election.

Of the facets of complexity that we have covered in this research, the changes to our social fabric are the most personally felt. But they follow the same pattern we’ve described in other areas. Rapid change introduces complexity to our lives, and that complexity serves as a headwind to our efforts to increase our productivity and, in turn, our prosperity.

But as we stated at the outset, our goal is not simply to quantify complexity in our lives, but discover the way past the paradox of prosperity towards better living. That path starts with awareness and knowledge of how to deal with the tectonic shifts taking place in technology.

Will tomorrow’s technologies transcend the paradox?

The thing with complexity is that it’s complicated. Complexity carries a cognitive burden that we experience whenever we observe the rapidly evolving world. The faster the world changes in terms of social conventions, technology, and commercial needs, the more we have to prepare for change. Every iteration of change is both an opportunity to excel and a risk of failure. No wonder there is so much anxiety.

So what is to be done?

One solution to the paradox of prosperity is to merely accept a simpler life even though that’s likely to entail lower productivity. The other solution is to master advanced technology to help bridge the gap between increased complexity and increased productivity.

Historically, new innovations, in particular communication technologies that enable new forms of connection and collaboration (from telegraph to radio to the Internet), have correlated to dramatic growth in global GDP. The advent of the telephone, for instance, led to widespread behavior change: a certain portion of a person’s time was now dedicated to connecting on the phone with friends, family, and customers.

Today, the “phone” we carry represents a massive focus of our time, for not only basic communication but also reading, information retrieval, photography, games, music, and so on. As with so many aspects of modern life, today’s technologies also represent a massive increase in complexity over what existed only a few years ago. First there is disruption, then widespread benefit.

What is interesting is that even though technology can cause complexity, it is also our best resource for simplification. We are only decades into the Internet era, while the impacts of artificial intelligence and robotics have barely been felt. Developments in computing, smart machines, and automation carry tremendous potential to directly improve people’s lives.

In recent years, technology has increased personal capabilities and productivity even as it has increased complexity. To take just one example, getting all our devices to seamlessly talk and sync with one another is a daunting task for most people. But there is a predictable cycle here. Today we’re in the early stage of the adoption of a long list of new technologies—from smartphones to artificial intelligence to social media to robotics. And, consistent with past adoption cycles, we’re in the difficult, sometimes confusing, disruptive stage. New capabilities carry a cost in complexity as we figure out how to fit them into our lives.

Current-generation technologies are powerful—powerfully capable and powerfully distracting—and in need of refinement. The good news is that we are at the cusp of a shift where that very technological capability starts to bring greater simplicity to our lives, as a new generation of technologies hides the technical complexity away behind screens and shells. Which leaves us with much simpler interfaces that make getting more accomplished faster and easier.

All of this relates directly to the paradox of prosperity. The generations-long changes we have described, the day-to-day complexity they have created, are at a tipping point. Much of this complexity can be untangled with advances in a new generation of technologies. When that refinement comes, all of the time we spend every day managing devices, fiddling with settings, troubleshooting problems, and so on will be freed up to spend however we want.

Advanced technology that insulates us from complexity will free up that time even as it helps us make better choices, ultimately empowering people to live and work better. And there we see the narrow path out of the paradox of prosperity: advances in artificial intelligence, robotics, biotechnology, and other technical areas that support a streamlined and simplified life, a life lived with meaning and purpose, that is savored not rushed, deep not shallow. Where we can be the best versions of ourselves.