If you’re above the age of 25 and you use Snapchat, there’s a good chance a teenager taught you how to navigate the youth-centric disappearing photo app. Snapchat became wildly popular after its 2011 debut, especially among users on the younger end of the millennial spectrum. But the app confounded most older users, giving even tech-savvy 30-somethings a taste of what it’s like to use tech products that cater to youth. Snapchat is just one example of the tech industry’s disregard for the needs and preferences of many older users. And that disregard is a big problem for everyone.

We’re all familiar with the trope of parents and grandparents relying on their kids to teach them how to turn on their computers or connect their smartphones to Wi-Fi. But beneath the joke lies a more substantial issue. Technology is often designed for the young, by the young, and the rest of the population is left to play catch-up.

That’s a problem, because as everyone becomes more reliant on technology for everything from buying groceries to accessing medical care, poor user experience design excludes people from important services. It’s also short-sighted from a business perspective, since a middle-aged executive likely has far more buying power than a smartphone-savvy teen. Yet many of our most commonly-used platforms seem to disregard usability factors for all but the youngest consumers.

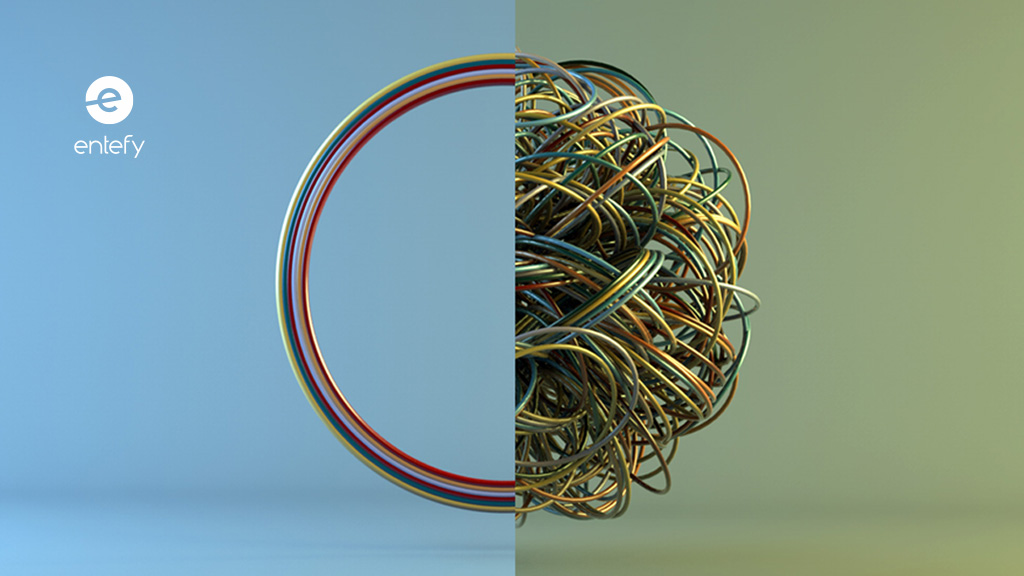

The digital chasm

In a given day, Americans check their phones 8 billion times a day, and the average person will spend five years of their lives on social media. Given all of that connectivity, you’d assume that the mobile apps that consume so much of our time are created with usability as the number one focus. Yet across many digital experiences, it’s clear that that’s not the case – especially if you’re older than 35.

At first glance, the youth-focused nature of tech design makes some sense. Research indicates that 18-34-year-olds show the highest rates of app downloads, time spent in-app, and device usage overall. Because they’re connected to a wide range of peers through social networks, they’re more likely to learn about and embrace new apps and digital products faster than older consumers.

While baby boomers and seniors are unlikely to outpace millennials on screen time (research shows that young users spend more time on their smartphones each day than they do with other people), smartphone and social media use is on the rise among older cohorts. One third of senior citizens use social media to get their news and entertainment, and 40% own smartphones.

Yet many older adults feel excluded from current technology trends. For instance, 77% percent say they would need help setting up a tablet or smartphone. Once they get online, however, many are quite active digitally and feel positively about their web experiences. Improved usability could extend the benefits of the Internet and mobile devices to a much wider range of people.

Despite this diversity, many tech platforms appear to be designed with little regard for older users. A digital native might intuitively know how to navigate the overwhelming number of features on a given platform. But millions of smartphone and social users didn’t grow up with these technologies, and designers aren’t making it any easier for them to adapt.

Ageist design on major platforms

Consider Facebook. When you open the page or app, you’re bombarded with activity from your friends and family. If you don’t get sucked into your constantly updating news feed, you may find yourself inundated with group and event listings, chat notifications, and friend recommendations for people you may or may not know. It’s easy to spend hours wading through all of the content and options. And many people do. The average Facebook user spends 50 minutes per day on the platform, nearly six hours per week. That’s 42.6 billion man hours per month given the platform’s 1.65 billion monthly active users.

But is the design user-friendly for all? Not so much. That’s why you see older users unwittingly posting personal messages as status updates or announcing to the world that they don’t know how to copy and paste. All of which indicates real usability problems – especially when you consider the privacy implications.

Even people who have used Facebook since its launch in 2004 gripe about its confusing privacy settings. As users become more aware of how their social posts impact their employment prospects and even their data security, they want more control over who sees what and when. Facebook has responded to demands for increased privacy control, but usability challenges persist for users already overwhelmed by the interface or how to manage their accounts.

But Facebook isn’t the only company that seems to take a less-than-inclusive approach to usability design. In recent years, critics have taken Apple to task for emphasizing aesthetics over functionality. Two of Apple’s earliest designers lambasted the company, which they say was once “a champion of the graphical user interface,” for abandoning “the fundamental principles of good design.” They say that in its quest for beautiful design, Apple created “obscure gestures that are beyond even the developer’s ability to remember.” And if a developer doesn’t find them intuitive, what chance does a late-adopter stand?

Then, of course, there’s Snapchat. One writer described his experience of attempting to use the app this way: “I end up flustered and sweating, haplessly punching runic symbols in a doomed bid to accomplish the basic task of viewing my friends’ messages before they expire. Snapchat, in short, makes me feel old.” Another put it even more succinctly, writing, “Snapchat has an age limit. But it isn’t set by asking you for your birthday. It is set through an interface that is so confusing you need to be young to get it.”

Not every app is going to appeal to every age group, and there’s nothing inherently wrong with catering to young users. But shouldn’t interfaces prioritize universal usability?

Inclusive design improves lives

Although baby boomers and senior citizens are slower to adopt new tech than their younger counterparts, it’s often not for a lack of desire. Data shows that older people are increasingly embracing new technology, especially products that accommodate the challenges of aging, such as vision impairment and arthritis. However, users over the age of 60 are reluctant to purchase smartphones because the “smaller screens and complex menus” are more difficult for them to use.

A move toward inclusive usability design has long-term benefits. Terry Bradwell, chief enterprise strategy and information officer at AARP, weighed in saying “As long as tech changes, there will always be a divide of some sort.” Most millennials grew up with constant connectedness, so while they’re not quite digital natives, they’re adapting OK – for the time being. But as we’ve witnessed in the past 20 years, technology is advancing at an unprecedented rate. Unless we begin prioritizing usability for all ages now, Snapchat will only be the tip of the iceberg in a generational technology divide.