Consider newborns. When we first lay eyes on the world around us, every sensation overwhelms our brains. There are colors, shapes, sounds, movement, and people totally unknown to us. Our brain does not yet know which of these experiences to prioritize and which to ignore, so our focus jumps from sensation to sensation. Slowly over time we learn to distinguish between the elements of our environment that are important and those that are not. We figure out how to properly filter the unceasing deluge of information swarming our senses. We grow up.

This filtering process is important because the brain does not respond well to being overworked. It prefers things to run smoothly and efficiently, which it does best when it is focusing on a few discrete items at once. Furrowed brows are the outward signs of brains at the limits of their processing capabilities. Many of the things we try to do with our brains will quickly test these limits—such as setting out to master advanced calculus or learning how to read sheet music. Only with experience and accumulated knowledge can our brains safely navigate learning with ease and efficiency.

When it comes to getting our information off the Internet, we’re all a little like children—we have limited attention and we’re not always sure where to direct it. It can be difficult to limit how much information we consume when there’s always something new waiting for a click. And then, before we know it, an abundance of messy and complex information has infiltrated our minds. If our processing strategies don’t keep pace, our online explorations create strained confusion instead of informed clarity. Focus is, after all, a finite resource.

Let’s take a look at how it all works, and how we can optimize the time we spend directing our focus.

Attention overload

One fascinating psychology study illustrates just how finite our attention can be. Researchers had participants watch a video of two groups of people passing a ball from person to person. One group wore white shirts, the other wore black. Participants were asked to count how many times those wearing white passed the ball. So far so good. But what initially seems like a task of ignoring the subjects wearing black takes an interesting turn when someone in a gorilla suit casually strolls into the scene, stands in the middle of the game, and thumps its chest. The gorilla, of course, should be an immediate distraction and easily noticeable, yet only half the participants spotted it. The conclusion: too many demands on our attention blind us to everything else.

Distraction has ties to forgetfulness. As we’ve explored previously, for humans to remember information, it must successfully survive the filtering processes of our sensory, short-term, and working memory systems. Only then can it be stored away in long-term memory. The place where we attend to and think about information is in working memory, and trying to jam too much information through this system leads to a substantial drop in performance, both in terms of processing the information and in storing it for later use. How much is too much? George Miller’s research in the 1950’s suggested that the limit was 7 items (plus or minus two), although more recent research has found that the magical number may be as low as 4. Which means that, structurally, the brain can only do so much at once. There goes multitasking.

Silicon Valley pioneer Mitchell Kapor has said that: “Getting your information off the Internet is like taking a drink from a fire hydrant.” On the Internet there’s a guide to everything, opinions abound, and there are more interesting facts and ideas than anyone knows what to do with. So much so that collectively we write as much in a day online as all the books in the Library of Congress combined. Where is this information storm taking us? And how is our limited attentional system going to keep up?

More information is not necessarily better information

There are now around 47 billion web pages online, while the number of Internet users has surpassed 3.5 billion. Meanwhile, a Nielsen report indicates that we spend an hour longer online each day now than we did just a year ago, with most of that increase coming from time spent on mobile devices. As more people jump on board, our reliance on the Internet grows. When Google went down for a few minutes in 2013, it took 40% of Internet traffic with it. Which isn’t that surprising when you consider that there are more than 58,000 Google searches every second. For better or worse, search engines have altered our behavior. In terms of our mental processing power, having answers so close at hand certainly reduces the cognitive load on our mental resources.

Yet when it comes to comprehending abstract concepts and making complex decisions, too much information causes its own set of problems. For instance, it can induce a feeling that we must read and consume more than is really required. We can get stuck in a stasis known as analysis paralysis, in which we set out to make a deliberate decision by considering every last detail, but instead get overwhelmed and struggle to make any decision at all.

The first study to document this effect came from Sheena Iyengar, a business professor at Columbia University. She set up a booth at a supermarket and offered samples of a selection of jams. She wanted to know how people would behave when presented with a selection of 6 jams compared to 24. What she found was that people initially responded favorably to the extra options—60% of people approached the booth, compared to 40% when only 6 jams were presented. But when it came to making a purchase, the figures reversed dramatically: 30% of people purchased from the selection of 6 jams, while only 3% purchasing from the larger selection.

Over time this effect compounds. The more choices we have to make, the greater the decline in the quality of our decisions. Psychologists refer to this effect as decision fatigue or mental fatigue, and one striking example of it comes from the judicial system, in which judges were found more likely to grant parole after having come back from a break and a bite to eat. Charted out over time, favorable rulings gradually dropped from around 65% to nearly zero, then returned to 65% after some rest. Rather than ruling case by case, the cumulative weight of making decision after decision eventually snowballed into mental exhaustion, making the judges less willing and able to properly evaluate cases later in the day.

For a more universal example, a 2010 survey of 1,700 professionals from the U.S., UK, China, South Africa, and Australia found that 59% of respondents had experienced a large increase in the amount of information they were required to process in the workplace, and 62% felt that the quality of their work suffered at times because of this information overload. Adding to this headwind against clear thinking, research out of Stanford University suggests that overthinking diminishes our creativity, making innovative solutions more difficult to come by.

Trying to tackle too much information clearly interferes with our ability to process the information effectively. This is a real concern in workplaces and schools, and whenever important life-decisions come about. Yet when it comes to the abundance of information we encounter on the Internet, it is not the only concern. Because this phenomenon we’ve taken to calling “fake news” impedes our natural ability to discern fact from fiction.

The informational wolf in sheep’s clothing

It’s not accidental that determining truth and reliability on the Internet is challenging. For every established website or expert that people feel they can trust, there are literally millions of others that we have never heard of and have no background information about. So when we scan through our feeds looking for something interesting to read, the content (subject matter) will often trump any evaluation of the source it comes from. To be fair, we hardly have the time to double check everything we read, yet the implicit trust we’re placing in total strangers is bound to backfire every now and again. Because what we read sticks.

Which brings us to the spread of fake news on social media, a problem that came into focus during the latter days of the 2016 U.S. presidential campaign. People were exposed to “news” items that looked legitimate—the provider appeared legitimate and the news itself may have even seemed probable. Yet it was fake. What is it about our brains that makes fake news possible? How did this whole issue come about?

It starts with how easy it is to assemble a beautiful, intuitive website quickly and with no knowledge of HTML. The Internet is populated with millions of good-looking blogs with snazzy logos and easy-to-use navigation. The problem with this is that psychologists have found that we inherently trust things that are simple and easy to use. This is another of the brain’s many shortcuts. Things (like websites) that we can use intuitively seem familiar, and familiarity breeds trust in our minds. And the lower the cognitive demand, the less critical we are of the information we’re taking in. Which provides absolutely no assurance that the information itself is reliable.

The Internet has made the whole of human knowledge instantly accessible. This is hardly a bad thing. But if we’re not careful in our information consumption strategies, we become susceptible to misdirection by misinformation. Just as we must learn as children how to filter our environment, we must learn as adults how to filter our information. So just how do we do this?

It comes down to changing habits

Our brains simply weren’t designed to handle the influx of information constantly bombarding us. So we need to find ways to filter and limit what we use. And move beyond efficiency and speed in information consumption to take into account the accuracy and reliability of the information itself. All of which starts with changing some habits.

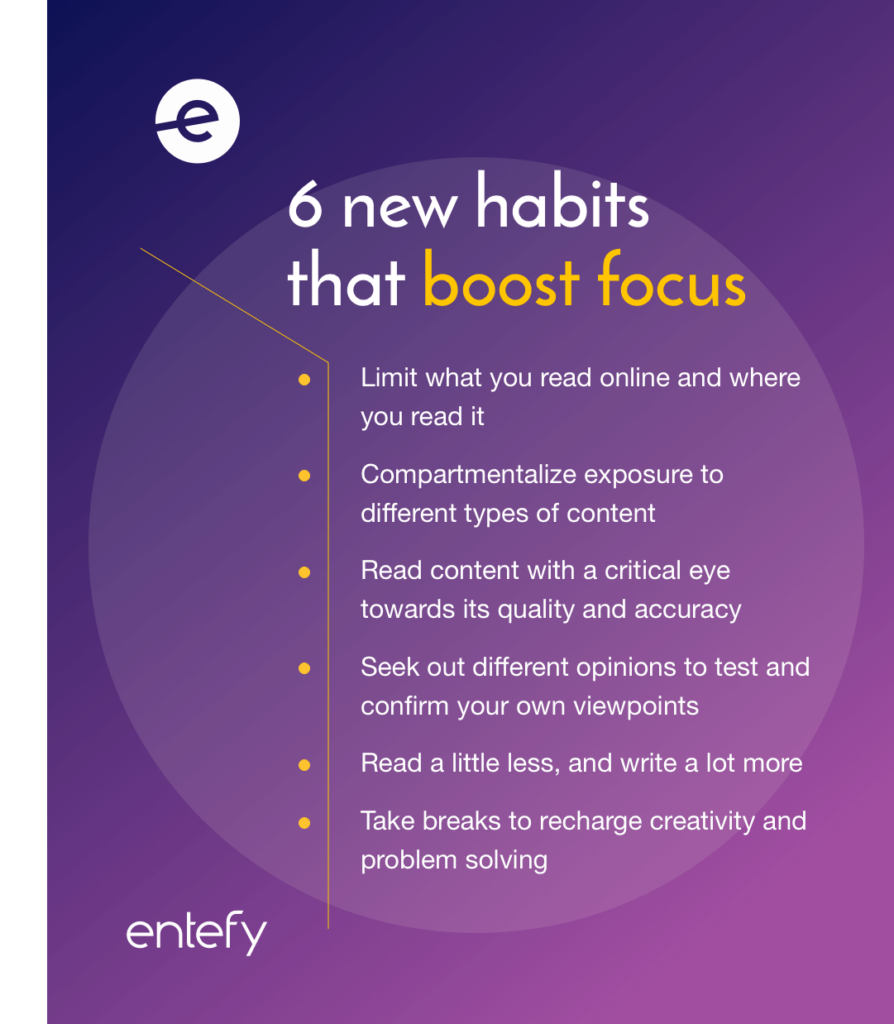

For starters, you can’t go wrong with simply limiting what types of information you see and where you see it. Every diet starts with consuming less. If you primarily use your social media accounts as a means to keep up with the goings-on of your friends and family, don’t also clutter those feeds with brands and celebrities. Compartmentalize social from news from entertainment, and consider using tools like RSS readers that consolidate a lot of different types of content into one place and provide easy tools for grouping and categorizing different types of media. And only ever follow sources you know, trust, and respect.

Next, unleash your inner critic. Teach yourself to simultaneously read an article while evaluating the support for the article’s premise—the claims, facts, and figure you’re reading about should be clearly backed by high-quality research or supported by multiple reliable sources. This improves the reliability of your personal list of trusted websites, publications, and people.

It’s also a good idea to purposefully investigate the opposite of what you expect or assume—people have a natural tendency to gravitate towards information that confirms their beliefs and ignore anything and everything that conflicts with them. This bias can lead us into an ideological bubble, a safe, warm, and self-sustaining echo chamber where we only ever see things that reconfirm our existing beliefs and preferences. When we step outside our comfort zone, we exercise our intellect in new ways and open up the door to discovery.

Another valuable tip for managing your information diet is to produce more than you consume. This can be done in several ways. Trying to generate an answer to a question before looking up the answers helps you remember the correct answer, even if your guess was well off the mark. And once you’ve read something interesting, take the time to summarize it and put it into your own words. Doing so helps you digest the material, spot the loose ends, and cement it in memory more effectively.

You also can’t get around something we’re often so busy we choose to ignore: take breaks. Research has shown that we are less able to find associations and links between facts and ideas when we’re tired, and sleeping (even if it’s only a nap) improves our recall of whatever we were learning before the break.

You might also be familiar with the notion of getting brilliant ideas while in the shower, and there’s research to back this up. It turns out that when we stop working on a problem, our brains continue processing in the background. As the study authors report: “Our data indicate that creative problem solutions may be facilitated specifically by simple external tasks (i.e., tasks not related to the primary task) that maximize mind wandering.” In order to store knowledge in our memory banks, it must be connected and associated with existing memories and prior knowledge. This unconscious process of creating connections sometimes leads to unexpected linkages—solutions to problems or radical new ideas.

It is easy to think that gaining more knowledge equates to consuming more information, but this isn’t the case. Knowledge asks more of us. It asks that we take the time to focus on quality, not quantity. That we ignore what is superfluous in order to focus on what’s important. That we take the time to connect new information with what we already know and understand. And, ultimately, that we leave behind sensory overload and learn to filter the meaningful from the noise. It’s how we grow up as information consumers.