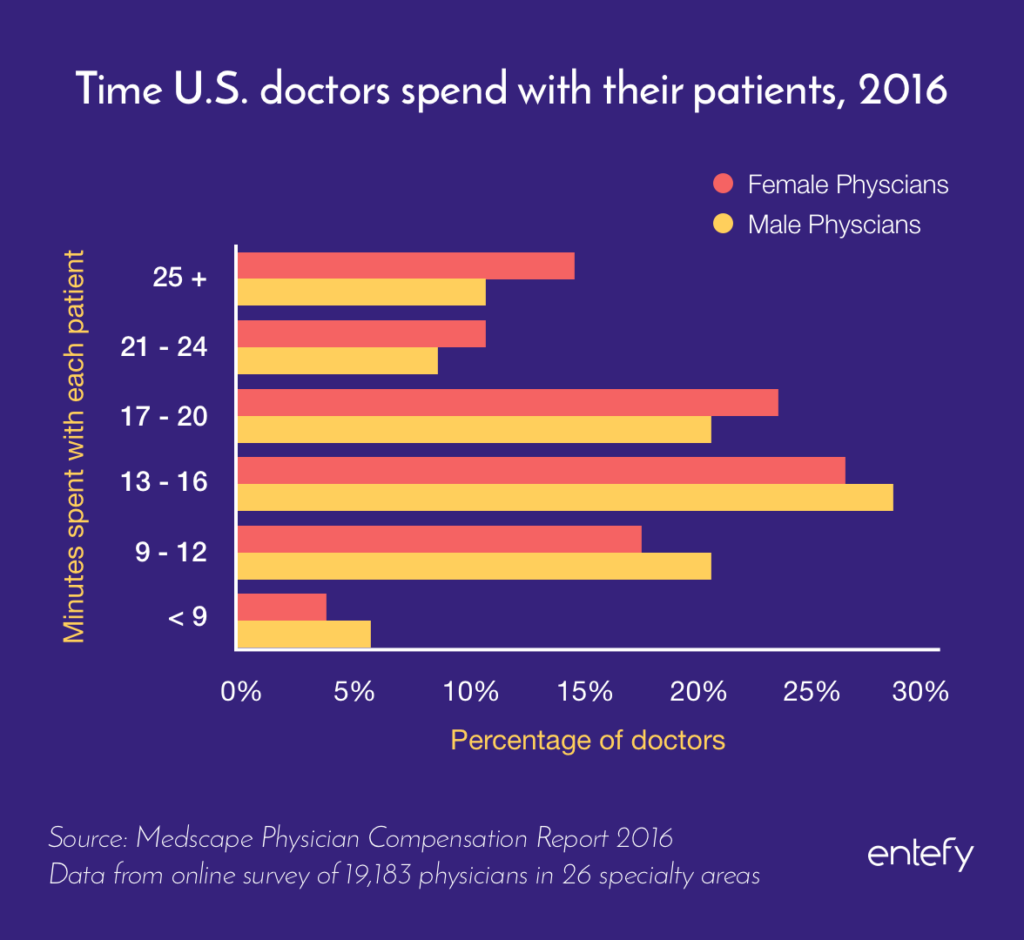

The World Health Organization has estimated that there is a global shortfall of approximately 4.3 million doctors and nurses, with poorer countries disproportionally impacted. In the U.S., these shortages are less acute; instead, the country struggles with ever-increasing heath care costs, which often translate into limits on the time a patient is able to spend with a doctor. One study estimated that U.S. doctors spend on average just 13 to 16 minutes with each patient.

Developments in the use of artificial intelligence technologies in medical care are beginning to demonstrate AI’s potential to improve the quality of patient care. Around the globe, researchers are studying how AI might become a new tool in the caregiver tool kit. From diagnosis, to personalized medical advice, to insights into genetics, AI is emerging as a new factor in medical care.

So against this backdrop of a global shortage in doctors and nurses, and cost-driven strains in patient care, let’s take a look at some of the ways AI systems are being evaluated for use in medical care.

Enhanced medical diagnosis

In August 2016, an artificially intelligent supercomputer did in 10 minutes what would have taken human doctors weeks to achieve. Presented with the genetic data of a 60-year-old Japanese woman suffering from cancer, the system analyzed thousands of gene mutations to determine that she had a rare type of leukemia.

The patient’s doctors had initially treated her for myeloid leukemia but observed that her recovery was unusually slow. They suspected that she had another form of the disease, but they knew it could take weeks for them to identify which of her thousand genetic mutations were relevant to her illness. Since speed is essential in effectively treating leukemia, the doctors used an AI system to run the analysis instead. Within minutes, the system determined that the patient had a secondary leukemia caused by myelodysplastic syndromes. Her medical team adjusted her treatment plan, and her condition improved soon after.

Arinobu Tojo, a professor of molecular therapy at a hospital affiliated with the University of Tokyo’s Institute of Medical Science said, “It might be an exaggeration to say AI saved her life, but it surely gave us the data we needed in an extremely speedy fashion.”

Elsewhere around the globe, scientists and doctors are making use of AI systems to tackle a long list of issues. Artificially intelligent computers are being designed to analyze gene mutations, make better use of scientific studies, and enhance doctors’ clinical knowledge beyond their first-hand experience.

One emerging theme for AI’s use in medicine: attempts to accelerate the pace of research breakthroughs. AI-driven research is taking place in areas as diverse as heart disease, diabetic complications, and brain trauma. One AI system is being used to analyze rare immunological conditions in children, providing physicians with insights on how to treat and cure issues that offer few clues at present. Machine learning is enabling much of these efforts.

Machine learning in medical care

The foundation for the use of artificial intelligence in medical care is machine learning, the process by which computers “study” huge datasets to discover insights. Physicians and machine learning scientists, for instance, supply a smart computer with archived medical photos to train the system to spot certain disease markers or mutations. The more data a machine-learning system has, the more adept it becomes at providing accurate results. The system learns by recognizing patterns and updating its analyses as it gains more information.

Researchers at Imperial College London are testing machine learning applications in treating traumatic brain injuries. When they fed their algorithm images of such injuries, the system identified brain lesions and learned to discern white and grey matter. That ability could provide researchers with valuable information about these life-altering and often fatal conditions.

In another example of machine learning applications in medicine, scientists recently experimented with how machine learning might facilitate diagnoses of diabetic retinopathy, a condition that causes vision impairment and blindness. The team trained the system using 128,000 images of healthy eyes. They then had the algorithm analyze 12,000 images and graded its ability to recognize signs of disease. The results indicated that the system “matched or exceeded the performance of experts in identifying the condition and grading its severity.”

Other implementations of machine learning are focused on the human genome, where AI systems are processing massive amounts of genomic data. The key to solving the mysteries behind conditions such as autism spectrum disorder lie in human genes, but the human brain simply can’t comprehend all the nuances and complexities of the genome. “I can say for sure that winning a game of Go is actually quite easy compared to understanding human health, and extending life spans, and saving lives,” says Brendan Frey, the co-founder and CEO of an AI genetics company and a professor of engineering and medicine at the University of Toronto.

Machine learning could be a game-changer in medicine because, unlike humans, computers don’t get tired and do have an infinite capacity for learning and memorization. They can process far more data far faster than even the most capable human physician. But that doesn’t mean that flesh-and-blood doctors are an endangered species.

Instead, AI is being designed to enhance diagnoses by providing doctors with data-driven insights derived from patients’ histories and conditions. Physicians can then use those reports to create treatment plans based on previously unavailable information. These systems can also provide vital insights in geographic areas where doctors, particularly specialists, are few and far between. Which, as the World Health Organization data reflects, is practically everywhere.

AI in the exam room

The breakthroughs in diagnosis and treatment we’ve been talking about may save lives and alleviate suffering for patients who live with life-threatening and chronic illnesses. But AI’s impact may also be felt in people’s day-to-day health management and routine doctor’s visits. Perhaps widening those brief 13 to 16 minute windows of time that patients spend with doctors.

One implementation of AI technologies in health care is taking place behind the scenes. Most of us have typed a list of symptoms into a web search at one point or another, and sorted through conflicting or alarming diagnostic information. Search companies are beginning to attach their platforms to AI systems with the goal of providing health information that is personally relevant. One study demonstrated that search histories can identify users who are at risk for pancreatic cancer and, potentially, other diseases.

Of course, search engines are not replacements for real doctors. But it’s arguably better to see results vetted by experts from Harvard Medical School and the Mayo Clinic than to scour questionable community forums that offer little in the way of knowledge or reassurance. Search platforms may also be able to nudge people to make appointments sooner rather than later when their searches indicate that they may be suffering from an illness.

Access to AI-powered medical databases could enable physicians to make more precise diagnoses because they would be drawing on a wealth of medical knowledge instead of thumbing through paper charts or trying to read through patient files during their already-short in-person visits. For instance, doctors at St. Jude’s Medical Center in Memphis and Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville currently receive pop-up notifications in patients’ digital files alerting them to potential contraindications with certain medicines.

The home-grown artificial intelligence system used at Vanderbilt University Medical Center predicts which patients may need specific drugs in the future. It can recommend that doctors run genetic tests on those who have a high likelihood of needing blood clot medications and other drugs, avoiding potential crises and saving time down the road.

AI is also being designed to help with disease prevention and management. Information pulled from hospital databases, electronic records, in-home monitors, fitness trackers, and implanted devices could help health care providers predict which patients show high indicators for conditions such as congestive heart failure (CHF). Mount Sinai Hospital in New York is already exploring how AI can help track patients who have or may develop CHF so they can prioritize care and help people manage their conditions.

Facilitating human connections

Let’s add some context to the “13 to 16 minute” doctor visit stat we cited earlier. One of the primary factors limiting doctor-patient time is something we’re all probably familiar with: paperwork. A study by the American Medical Association followed a group of 57 physicians through 430 hours of patient care. Here’s what it found:

Physicians spent 27% of their time in their offices seeing patients and 49.2% of their time doing paperwork, which includes using the electric health record (EHR) system. Even when the doctors were in the examination room with patients, they were spending only 52.9% of the time talking to or examining the patients and 37.0% doing […] paperwork.

For all of the potentially groundbreaking research we’ve described here—into diseases, genetics, diagnostic automation—the true test of AI’s impact in medical care might be whether it can make a dent in the paperwork problem. Medical records, regulatory documentation, insurance filings, you name it. Because in one pass, you free up time that doctors and nurses can devote to patient care; and perhaps even attract more people to the professions, addressing the global doctor shortage.

AI-driven efforts are already underway to combat the administrative burden. Some health companies are using apps to cut down on the time nurses and doctors spend gathering patient information. Outsourcing triage and patient interviews to algorithms could cut down on health care costs, but with the risk that this could further reduce the time doctors spend with their patients. The goal would be to improve doctor-patient interactions by freeing physicians from laptop screens and focusing on the people in front of them.

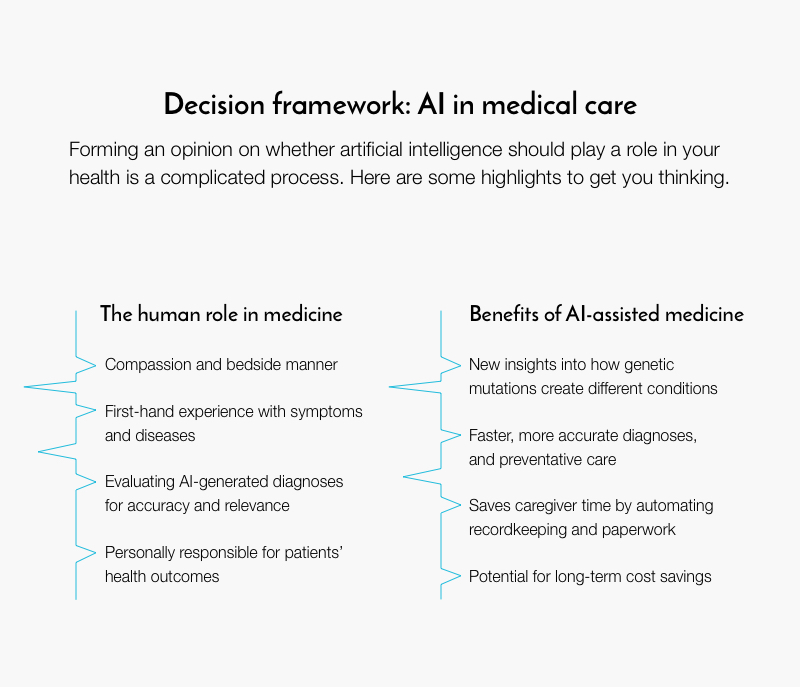

And that’s really where the true potential of AI in medicine lies. Rather than replace interpersonal connections and involvement, AI can reduce the burden on doctors and nurses so they can focus on the uniquely human elements of patient care. No one will complain if AI helps lower health insurance premiums or helps physicians find the right treatments faster. But people look to doctors and nurses for reassurance, comfort, and insight. Machines simply cannot replicate a human’s bedside manner.

It’s not an all-or-nothing decision, either. While algorithms can generate comprehensive analyses of a patient’s history and suggest a potential diagnosis, doctors need to evaluate that information and apply their real-world experience to determine the course of care. It’s also worth noting that at present smart machines cannot explain the reasoning behind their suggested diagnosis, so doctors can’t know whether the process behind their recommendations is sound. They can use the information to supplement their own analyses or as a jumping-off point when working out a diagnosis. The responsibility for patient care is their own.

Ultimately, AI has the potential to enhance the practice of medicine, from disease research to the logistics of routine care. But its greatest impact may be found in how it enhances and empowers human practitioners.

Additional article contributors: Mehdi Ghafourifar and Brian Walker.