Abstract

In 2025, foundation models are undergoing meaningful capability expansion beyond scale alone, incorporating broader agentic functionalities, spatiotemporal reasoning, domain expansion, and more rigorous evaluation under realistic constraints. Prior surveys have largely emphasized benchmark performance and scaling trends, but they rarely expand upon four emerging research trends: (1) the rise of agentic multimodal models capable of both planning and acting, (2) the extension of foundation models into time series and sequential non-textual data domains, (3) the push for ever-increasing context lengths, mixture-of-experts (MoE) architectures, and efficiency trade-offs, and (4) the need for improvements to model evaluation, robustness, and safety. This article addresses these gaps by synthesizing recent works across these dimensions, situating them within a broader trajectory from “understanding” to “acting,” and identifying open research directions that are tractable yet impactful. Specifically, this article highlights the need for frameworks that address graceful degradation, long-context memory architectures, robustness benchmarks for agentic tasks, interpretability in planning, and on-device efficiency. By reframing the frontier of foundation models around reliability and real-world deployment, this article provides a roadmap for the next phase of foundation model research.

Introduction

Foundation models are large pre-trained models designed for reuse across tasks and they have been evolving rapidly. In earlier years, research broadly emphasized scaling model size, often by collecting more training data, as a primary method of improving benchmark performance. In 2025, much of the focus in frontier model research has been more targeted, emphasizing improved performance on specific generalizable capabilities (e.g. action, planning), context scaling, inference efficiency, and evaluation under realistic constraints (e.g., modality noise, deployment hardware, etc.).

Several surveys have offered valuable overviews of foundation model research. For example, Bommasani et al., (2021) introduced the concept of foundation models and emphasized opportunities and risks associated with scaling. More recent surveys have examined specific dimensions such as resource efficiency, agentic AI evolution, human-centric foundation models, and recommender systems powered by foundation models. However, these surveys often focus on one or two axes in isolation without fully integrating them into a coherent end-to-end picture.

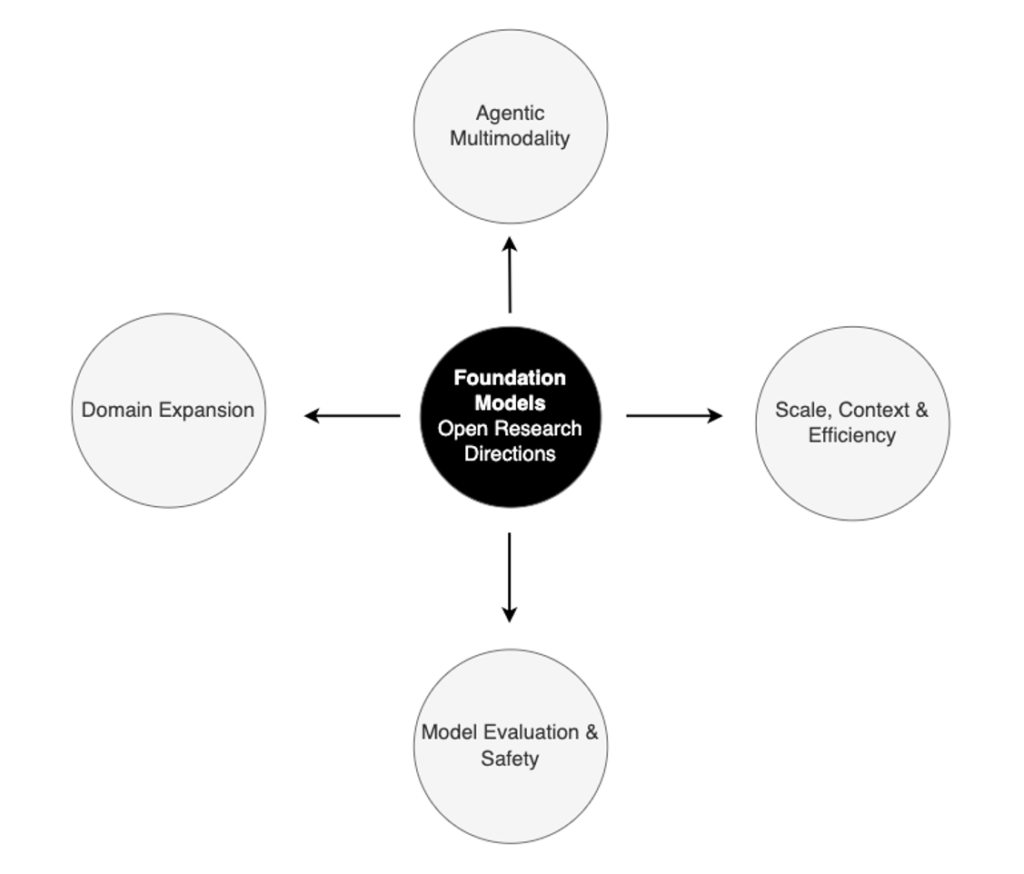

This paper addresses recent areas of foundation model advancement across four major axes:

- Agentic Multimodality for planning and acting, where models move beyond passive perception, to planning and action

- Domain Expansion into sequential and non-textual data domains such as time series, finance, and sensor data

- Scale, Context and Efficiency with innovations in long-context memory, mixture-of-experts architectures, and resource optimization

- Model Evaluation and Safety, encompassing robustness under noise, lifecycle assessments, adversarial testing, deployment constraints, and accountability practices

Open research directions emerge from the interplay of these four axes, highlighting tractable priorities such as graceful degradation, interpretability of planning, efficient edge deployment, and standardized evaluation benchmarks. Together, these themes define the shift from scale-driven benchmark chasing toward reliability, transparency, and safe real-world deployment.

Figure 1: Overview of emerging research axes in foundation models: (1) Agentic Multimodality, (2) Domain Expansion into sequential and non-textual data, (3) Scale, Context, and Efficiency, and (4) Model Evaluation and Safety. Open research directions emerge at their intersections, signaling a shift from scale-driven progress to reliability and real-world deployment.

Agentic Multimodality

The first axis of progress in foundation models is the shift from passive multimodality, perception across vision and language, toward active agentic multimodality, where models can reason, plan, and act in diverse digital and physical environments. Recent academic studies demonstrate this transition across robotics, embodied reasoning, and virtually any domain that uses computers. For instance, EmbodiedGPT (Mu et al. 2023) integrates large language models (LLMs) with planning via an embodied chain-of-thought, improving long-horizon control in simulated robotics tasks. In another study, OpenVLA (Kim et al. 2024) provides an open-source vision-language-action model trained on large-scale robot demonstrations, offering a transparent academic baseline for generalist manipulation. In parallel, StarCraft II Benchmarks (Ma et al., 2025) demonstrate how agentic combinatorial vision–language models can handle decision-making in dynamic, adversarial environments.

Finally, broader surveys such as the Agentic LLM Survey (Plaat et al., 2025) situate these developments within a general framework of models that not only perceive and generate but also reason, act, and interact. Collectively, these works mark a clear transition from research in vision-language models toward a combination of vision, language, action, planning, and temporal reasoning models. This shift positions the capability to act as a central axis of foundation model research. Table 1 summarizes early agentic foundation models.

Table 1. Comparison of Early Agentic Foundation Models

| Model | Core Capability | Distinctive Features | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| EmbodiedGPT | Vision–language–action reasoning | Embodied chain-of-thought, long-horizon control | Simulation-only, limited real-world tests |

| OpenVLA | Vision–language–action policy learning | Open-source, large-scale demos | Focused on manipulation tasks |

| StarCraft II Benchmarks | Multimodal decision-making | Tests agentic reasoning in dynamic, adversarial play | Domain-specific, limited transferability |

Domain Expansion

Complementing the agentic shift, another emerging axis involves the extension of foundation models beyond language and vision into non‑standard data domains, especially time series where robustness and noise present unique challenges. The survey conducted by Rama et al.(2025) offers a taxonomy of Time Series Foundation Models (TS FMs), discussing model complexity and distinguishing among architecture choices such as patch‑based vs. raw sequence data handling, probabilistic vs. deterministic outputs, univariate vs. multivariate inputs. Complementary to that survey, Gupta (2025) probes how well these models handle long‑horizon forecasting under noise, periodicity, and varying sampling. The research finds that while TS FMs outperform classical statistical baselines under favorable conditions, performance degrades as noise rises, sampling becomes sparse, or periodic structure grow more complex. Further, Lakkaraju et al. (2025) introduces a framework for evaluating TS FMs in financial domain tasks (e.g., stock prediction), comparing multimodal vs. unimodal models, and showing that models pre‑trained specifically for time series are more robust than general‑purpose foundation models.

Beyond time series, research shows momentum in several other domains:

- Structured and tabular data. Recent work on tabular foundation models demonstrates the feasibility of pretraining on large collections of tables with semantics-aware objectives. Examples include TabICL (Qu et al., 2025), TabSTAR (Arazi et al., 2025), and TARTE (Kim et al., 2025), which explore target-aware conditioning, in-context reasoning, and semantic alignment across rows and columns. Klein & Hoffart (2025) further argue that foundation models for tabular data need grounding within systemic contexts rather than treating tables as isolated objects.

- Graphs and relational structures. The survey by Wang et al. (2025) provides a comprehensive overview of graph foundation models (GFMs), covering architectures, training regimes, and challenges in applying foundation model paradigms to relational data such as knowledge graphs, citation networks, and drug–target interactions.

- Scientific and molecular domains. Cantürk et al. (2024) outline opportunities and obstacles in building molecular foundation models, highlighting the role of large-scale molecular datasets and multimodal signals (e.g., chemical graphs, protein sequences, text from scientific papers). These directions illustrate how foundation model principles extend into biology, chemistry, and materials science.

Collectively, these works illustrate that foundation modeling is extending well beyond language and images into temporal, structured, relational, and scientific domains. Yet across these domains, common fragilities emerge including performance degradation under noise, domain shift, sampling irregularity, missing modalities, or adversarial perturbations. Building resilient and interpretable models for such high-stakes, heterogeneous data remains an open challenge.

Scale, Context, and Efficiency

Alongside domain and capability expansions, progress continues scaling context windows, rethinking architectures, and improving efficiency, resulting in developments that reshapes what is computationally feasible.

One of the high‑visibility developments is LLaMA‑4 (Scout and Maverick variants) from Meta. The LLaMA‑4 introduces MoE architecture and is natively multimodal (text and image inputs). It supports extremely long context windows as well. Scout supports up to ~10 million tokens active (~109B total parameters, ~17B activated), while Maverick includes even more experts and ~1 million token context (Meta AI, 2025). These advances matter because many downstream tasks (e.g., legal, scientific, long documents, context‑rich conversations) require long-context reasoning. Prior models often capped at tens or a few hundreds of thousands of tokens.

Moreover, infrastructure and licensing updates also reflect these trends. In mid‑2025, the Qwen3 family reported a 235B model with 256,000 token context length in release notes (Qwen, 2025). The flagship Qwen3-235B-A22B model has 235 billion total parameters, with 22 billion activated parameters per input, while the smaller variant Qwen3-30B-A3B has a total of ~30 billion parameters, with ~3 billion activated parameters.

Efficiency involves more than memory or context, it includes active versus total compute, parameter sparsity, quantization, and model deployment. MoE architectures (e.g., LLaMA‑4) support large parameter counts while activating only subsets per input, theoretically lowering inference cost. However, MoE introduces challenges such as load balancing, routing overhead, and expert collapse. While there is growing attention to quantization, compression, and optimization for on‑device or resource‑constrained settings, public results remain limited (Xu et al., 2024).

Model Evaluation and Safety

These advances raise the stakes for evaluation. As models become more capable and agentic, measuring robustness, safety, and degradation under realistic conditions becomes central.

First, recent work in time series (Gupta, 2025; Lakkaraju et al., 2025) emphasizes robustness to noise, domain shift, and irregular sampling. The causally grounded rating methodproposed by Lakkaraju et al., (2025) offers a structured method to compare robustness in ways interpretable by stakeholders, especially in high risk financial contexts.

Second, agentic multimodal models extend evaluation beyond traditional benchmarks by testing on tasks such as UI navigation and robotic manipulation, where errors have tangible digital or physical consequences.

Finally, industry efforts are beginning to incorporate red-teaming, misuse risk assessments, and documentation standards into model releases. For example, Anthropic’s Claude family and OpenAI’s GPT series include published evaluations of model behavior under adversarial prompts, while Meta has introduced model cards detailing limitations and deployment considerations (Anthropic, 2024; Meta AI, 2025; OpenAI, 2025). Although uneven, these practices show a shift from narrow leaderboard focus toward a broader assessment of robustness, safety, and accountability.

Taken together, these developments illustrate that evaluation of foundation models is moving from a fragmented set of benchmarks toward a more diverse ecosystem of frameworks. Table 2 compares the main categories of evaluation approaches, highlighting their focus areas as well as their limitations.

Table 2. Emerging Frameworks for Evaluating Foundation Models

| Category | Focus | Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| Academic frameworks | Robustness under noise, domain shift | Often limited to specific domains (e.g., time series), not standardized |

| Agentic multimodal benchmarks | Evaluation on robotics, UI navigation, embodied tasks | Early-stage; task-specific, lack large-scale standardized benchmarks |

| Industry system cards | Red-teaming, adversarial robustness, risk disclosures, model limitations | Uneven transparency, focus varies across companies |

| Regulatory/third-party reports | Lifecycle evaluations, accountability, socio-technical risks | Policy-oriented, less technical detail for benchmarking |

Synthesis of Trends and Observations

From the foregoing, several narrative arcs define current foundation model research.

- From understanding to acting. Action grounding and agentic behavior are becoming core capabilities rather than add‑ons. This raises demand on data (e.g., videos, robotics trajectories), architectures (e.g., grounding, temporal modeling), and evaluation.

- Exploding context window. Longer context windows are rapidly becoming a necessary condition for many tasks. Recent LLMs’ million‑token contexts now set expectations for scientific, legal, and enterprise tasks.

- Domain expansion. Time series, financial forecasting, robotics, UI navigation are gaining more attention. The classic text and image paradigm is no longer sufficient for many real‑world systems. With that extension come new challenges such as irregular sampling, missing modalities, noise, and domain shift.

- Robustness, noise, and modality gaps. Several studies indicate sharp performance degradation under realistic conditions, for instance high noise, missing modality, or sparse sampling. These are often under-investigated in earlier benchmark‑driven work.

- Importance of efficiency & deployment constraints. Architectural techniques such as MoE, quantization, and sparse activation are growing. Device constraints such as latency, memory, and inference cost are no longer afterthoughts, especially for agentic or interactive models.

- Evaluation, safety, and accountability. Benchmarking through adversarial, safety, and regulatory lenses are becoming priorities and are increasingly part of publication and release practices.arcs define current foundation model research.

Taken together, these arcs paint a landscape where foundation models are expected not only to scale but also to act reliably, generalize across modalities, and operate under real-world constraints. Table 3 summarizes the converging directions, their key narrative arcs, and the unresolved questions and tensions.

Table 3. Synthesis of Recent Trends in Foundation Models

| Narrative Arc | Implications | Open Tensions |

|---|---|---|

| From understanding to acting | Agentic behavior is becoming central rather than peripheral, requires multimodal and temporal data | How to ensure safe and reliable action across both digital (UI) and physical (robotics) domains? |

| Exploding context window | Million‑token contexts now set expectations for scientific, legal, and enterprise tasks | Maintaining coherence, avoiding hallucinations, and managing inference cost at scale |

| Domain expansion | Extension to finance, health, and sensor data reveals fragility under noise and irregularity | Lack of standardized, realistic benchmarks for non-textual domains |

| Robustness, noise, and modality gaps | Studies highlight sharp performance degradation under missing or noisy inputs | Balancing efficiency with reliability, avoiding expert collapse in MoE |

| Evaluation, safety, and accountability | Model lifecycle documentation and red-teaming are becoming expected in releases | Standards are uneven, voluntary, and not yet institutionalized across industry |

Open Questions and Research Directions

Despite recent advancement, several gaps remain, and some research directions are particularly promising:

- Modality drop & graceful degradation. How do agentic multimodal models perform when modalities are missing or corrupted? Can architectures or training regimes be designed to learn fallback strategies?

- Attention & memory architectures for very long contexts. Even with context windows of more than one million tokens, maintaining coherence, avoiding hallucinations, and managing inference costs remains challenging. Theoretical bounds on trade‑offs (context length vs. compute) would help.

- Robust evaluation benchmarks. Benchmarks remain scarce for agentic tasks that combine vision, text, and action with realistic noise or adversarial perturbations.

- Data quality, bias, and safety in agentic and spatial tasks. Data sources for robotics, UI navigation, and instructional videos often have biases and gaps. Safety in physical settings (e.g., robot manipulation) is especially risky. Ensuring safety during filtration and annotation of data remains challenging.

- Interpretability and transparent planning. When models plan or act, how do we inspect or verify what internal representation or plan they used? Methods for extracting and verifying reasoning trajectories (e.g.,Trace of Mark (ToM), Chain of Tought (CoT)) are underdeveloped.

- Efficient on‑device/edge models for agentic tasks. Many agentic tasks will need to operate under resource constraints (e.g., mobile devices, embedded systems). Designing architectures that balance model size, latency, and energy with action accuracy is an open problem.

- Regulatory compliance, model cards and risk documentation. Establishing standard practices to release foundation models with clear documentation of failure modes, safety risks, data sources, and licensing constraints.

Conclusion

The trajectory of recent foundation model research reflects a shift from an era dominated by scale and benchmark performance toward one centered on capability breadth, robustness, and deployment realities. Models are judged not only by their ability to process language or images, but also by whether they can plan, act, and reason over long horizons in noisy, incomplete, and hardware-constrained environments.

This study reviews the progress in the areas of Agentic Multimodality, Domain Expansion, Scale and Efficiency Innovations, and Evaluation and Safety Frameworks. These domains are usually treated separately in prior surveys. Furthermore, this study provides comparative analysis by contrasting leading models and evaluation frameworks across academic, industry, and regulatory contexts. And finally, it outlines a forward-looking roadmap by identifying tractable yet impactful research directions.

Taken together, these contributions point toward a maturing field where the central question is no longer “how do we scale further?” but rather “how do we make foundation models reliable, interpretable, efficient, and safe in the wild?” The coming years will determine whether foundation models fulfill their promise as broadly useful, trustworthy systems, or remain fragile benchmark performers.

ABOUT ENTEFY

Entefy is an enterprise AI software company. Entefy’s patented, multisensory AI technology delivers on the promise of the intelligent enterprise, at unprecedented speed and scale.

Entefy products and services help organizations transform their legacy systems and business processes—everything from knowledge management to workflows, supply chain logistics, cybersecurity, data privacy, customer engagement, quality assurance, forecasting, and more. Entefy’s customers vary in size from SMEs to large global public companies across multiple industries including financial services, healthcare, retail, and manufacturing.

To leap ahead and future proof your business with Entefy’s breakthrough AI technologies, visit www.entefy.com or contact us at contact@entefy.com.