Abstract: Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly deployed in high-stakes contexts, yet their trustworthiness remains uncertain when ethical principles, technical mechanisms, and governance structures operate in isolation. This paper reviews the current landscape of trustworthy AI, including work on ensuring fairness, eliminating bias, explainability, privacy protections, trust in models, governance, and legal accountability. It further describes persistent challenges that limit reliability under real-world conditions. It identifies an operational integration gap and proposes to address this gap by the Unified Accountability Framework (UAF), a holistic, 5-tier approach for operationalizing trust in the era of foundation models. The five tiers of the UAF include Foundational Principles, Governance Structures, Lifecycle Integration, Technical Assurance Tools, and External Accountability. Trustworthy AI should be understood as an evolving sociotechnical phenomenon in which normative commitments, technical verification, and institutional oversight evolve to sustain legitimacy and adoption. In doing so, the framework provides a pathway for translating ethical intent into verifiable and governable trust across the AI lifecycle.

Keywords: Ethical AI; Trustworthy AI; Foundation Models; AI Governance; Socio-technical Trust, Accountability Frameworks

Introduction

Recent years have seen a rapid expansion of foundation models and generative systems, from research prototypes to deployed commercial products with significant societal impact. Across many domains including clinical diagnostics, judicial risk assessment, creative media, and autonomous mobility, ethically sensitive applications of AI are no longer speculative; they are now deployed in contexts where errors or biases can have harmful consequences. Against this backdrop, the notion of “trustworthy AI” has become central, invoked by policymakers and researchers across disciplines (Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, 2019; Tabassi, 2023).

Trustworthy AI is commonly defined through overlapping principles of fairness, transparency, privacy, accountability, and ethical alignment (Floridi & Cowls, 2019; Jobin et al., 2019). A short list of the most important domains where AI is being applied and raises unresolved issues of bias and fairness includes healthcare and clinical decision-making, hiring and workplace management systems, criminal justice and policing, credit, lending, and insurance, and public benefits and housing allocation, all of which directly shape life chances and embed historical inequalities into automated decisions. The ethical principles that will govern fairness and bias in AI are being shaped through an ongoing debate among ethicists, government regulators and legislators, courts and administrative bodies, industry actors and technical standard-setting organizations, civil society and advocacy groups, and domain experts such as clinicians, HR professionals, financial experts, and public administrators, whose combined judgments will determine which principles are salient and how they are applied in practice.

As these discussions and debates proceed, an important operational integration gap has emerged. How will these emerging normative principles move from abstract consensus to operational design? How will these principles be concretely embedded in the architecture, training data, objectives, constraints, and governance processes of each AI system? The answers to these questions can guide how fairness is enacted by the system itself rather than imposed only after deployment.

To address this operational integration gap, this paper introduces the Unified Accountability Framework (UAF), a model that frames trustworthy AI as a sociotechnical continuum. As further described later in this paper, the UAF represents a 5-tier approach that determines the legitimacy and resilience of AI systems, as follows:

- Foundational Principles define the ethical and normative grounding of the AI system, serving as the basis for all downstream processes to ensure fairness, accountability, transparency, and privacy. These Foundational Principles are those which will emerge ultimately from the ongoing debates about salient ethical principles and how they will be applied. In this paper, we summarize the current state of these debates. These principles will develop and evolve over time, but we find utility in taking the current state of affairs as the starting point for the UAF.

- Governance Structures establish institutional mechanisms to embed end-to-end ethical oversight.

- Lifecycle Integration operationalizes principles and governance through structured processes across the entire AI lifecycle.

- Technical Assurance Tools include the technical toolkits and standards necessary for implementation.

- External Accountability ensures the system is aligned with societal and regulatory expectations.

This paper makes three primary contributions to advancing the study of trustworthy AI. The primary contributions include:

Current Research Landscape and Challenges: Synthesizing recent research across four key dimensions, i.e., fairness and bias, explainability and privacy, trust assessment for foundation and generative models, and governance and legal accountability, embedding the key challenges and gaps directly within each dimension rather than treating them separately.

The Case for Trustworthy AI: Examining how issues of trustworthiness manifest in practice through various areas of study including healthcare, autonomous vehicles, generative AI, and facial recognition, identifying both technical advances and persistent limitations.

The Unified Accountability Framework (UAF): Proposing a unified framework for operationalizing trust by coupling ethical principles, technical mechanisms, and governance structures within an auditable feedback system. The UAF offers a scalable model for integrating normative, computational, and institutional approaches to trustworthy AI in the era of foundation models.

Together, these contributions provide a synthesized understanding of the current research landscape and a forward-looking framework for developing AI systems that are robust, transparent, and societally legitimate.

The Current Research Landscape and Challenges

Four interrelated dimensions accurately characterize the current research landscape: fairness, explainability, trust assessment, and governance. Despite limited progress in each dimension, major challenges remain.

Table 1 below highlights both the breadth and the fragmentation of contemporary research on trustworthy AI. Fairness has produced relatively mature toolkits, whereas explainability remains marked by unresolved trade-offs with privacy. Trust assessment frameworks are still in early stages of standardization, and governance continues to struggle with enforceability. These observations motivate a closer examination of each of these four dimensions. The following subsections analyze fairness, explainability, trust assessment, and governance in greater depth, focusing on both recent advances and the persistent gaps that constrain their practical effectiveness.

Table 1. Advances and Challenges Across Core Dimensions of Trustworthy AI

| Dimension | Advances | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Fairness | Debiasing method | Metric incompatibility, poor generalization, lack of cross-cultural evaluation |

| Explainability | Recourse explanations, layered Explainable AI (XAI) | Privacy leakage, one-size-fits-all design, lack of evaluation standards |

| Trust Assessment | Benchmarks and robustness testing | Focus on average-case, lack of formal guarantees, scalability issues |

| Governance & Law | EU AI Act, NIST RMF, audits | Enforcement gap, legal-technical mismatch, accountability diffusion |

Fairness, Bias, and Multimodal Ethical Concerns

Fairness has become one of the most extensively studied areas in trustworthy AI, with technical approaches spanning data balancing, fairness-aware optimization, and post-hoc adjustments (Mitchell et al., 2021). Yet this body of research reveals fundamental challenges which have yet to be solved. For instance, surveys of multimodal systems such as vision–language models document persistent representational bias and stereotyping. Captioning and Visual Question Answering (VQA) models often misinterpret ethnicity or gender, and even when debiasing strategies improve performance on a benchmark dataset, they frequently fail to generalize to new distributions (Saleh & Tabatabaei, 2025). Similar observations appear in surveys of multimodal fairness that classify biases and evaluation methods across image, text, and speech systems (Booth et al., 2021; Mehrabi et al., 2021). This difficulty points to the broader challenge of fairness under domain shift: what appears “fair” in one dataset may collapse in another.

Compounding this, different fairness measures can conflict with each other, optimizing for one (e.g., predictive parity) can reduce performance on another (e.g., equalized odds). Therefore, deciding what “fairness” means in practice involves ethical judgment and policy choices, not just technical optimization (Corbett-Davies et al., 2023). Studies in multimodal biometrics also show that demographic disparities persist even when multiple modalities are combined, indicating that multimodality does not automatically eliminate bias (Fenu & Marras, 2022). Operational tools such as Fairlearn (Weerts et al., 2023) help practitioners evaluate disparities across metrics, yet adoption reveals another gap. Organizations often lack guidance on which definitions of fairness align with their specific obligations or contexts. Surveys of fairness methods in applied AI (Yang et al., 2024) show that most strategies remain dataset-specific and struggle to generalize beyond benchmarks, a limitation consistent with findings in multimodal tasks. Finally, cross-cultural and low-resource settings remain underexplored. Much of the fairness literature relies on English-language data and high-resource domains, while multilingual and culturally diverse scenarios, precisely where bias is most consequential, receive limited attention.

Explanability and Privacy Trade-offs

Explainability is a pillar of trustworthy AI, yet recent work shows that explanations themselves introduce new risks. Attribution maps, example-based rationales, and internal gradients can leak sensitive information, creating privacy vulnerabilities that adversaries may exploit (Allana et al., 2025). This tension between transparency and privacy remains poorly quantified. Few systems measure both explanatory fidelity and information leakage risk, leaving practitioners without clear trade-off curves. What reassures a regulator may overwhelm a clinician, while a patient may require a different form of reasoning. The classic “one-size-fits-all” challenge persists in the explainability dimension. Without careful tailoring, explanations risk being too shallow to foster trust or too complex to be usable. Alongside these human-centered advances, recent research promotes actionable, recourse-oriented explanations that show users concrete steps they might take to change outcomes (Fokkema et al., 2024). Other studies conceptualize recourse as minimal interventions rather than simple counterfactual shifts (Karimi et al., 2021). Yet evaluation standards remain unsettled. Distinguishing between faithfulness to internal mechanics and plausibility for human audiences is still not practiced consistently (Leiter et al., 2024).

Trustworthiness Assessment for Generative & Foundation Models

The emergence of foundation and generative models has catalyzed a shift toward more systematic assessment frameworks. Traditional metrics such as accuracy or perplexity offer limited insight into whether these systems are safe, robust, or equitable. In response, TrustGen (Huang et al., 2025) introduced a benchmarking platform that evaluates generative models across fairness, robustness, transparency, and safety dimensions, revealing consistent weaknesses in low-resource languages, rare prompts, and adversarial settings. These findings reinforce a long-standing concern that most evaluations capture only average-case performance, whereas trust requires resilience under worst-case scenarios. Recent surveys document advances in adversarial robustness and privacy-preserving techniques, yet most defenses remain empirical, narrow in scope, and rarely extend to multimodal or generative architectures (Goyal et al., 2023; Li et al., 2024; Meng et al., 2022). Formal guarantees such as certified robustness bounds remain uncommon, leaving practitioners reliant on heuristics that often fail to generalize in deployment. Benchmark scalability also remains a persistent challenge, as new model families evolve faster than evaluation platforms can adapt. This phenomenon increases the risk of standards lagging behind real world model development and evolution (Bommasani et al., 2021; Bortolussi et al., 2025; Dong et al., 2025). In high stakes domains such as healthcare, this mismatch is especially evident. Recent AI and LLM application guidance in health emphasizes traceability, transparency, and human oversight, yet current benchmarks seldom incorporate such lifecycle assurances (Freyer et al., 2024; Guidance on the Use of AI-Enabled Ambient Scribing Products in Health and Care Settings, 2025).

Governance, Auditing, and Legal Interfaces

Governance efforts have proliferated, with the EU (European Union) AI Act (EU AI Act: first regulation on artificial intelligence, 2025) and NIST AI RMF (Artificial Intelligence Risk Management Framework: Generative Artificial Intelligence Profile, 2024) defining risk-based frameworks, and industry actors issuing their own responsible AI principles. NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce. Surveys of AI researchers depict a torn community, one that broadly supports investment in safety and accountability research and another that remains divided on issues such as restricting military applications (Grace et al., 2017). Despite this momentum, an enforcement gap persists. Principles are abundant, yet mechanisms for independent monitoring and compliance remain limited. Accountability is especially diffused in open-source ecosystems, where responsibility for downstream harms often remains unclear. At the legal frontier, debates over copyright and data provenance have intensified. Henderson et al. (Henderson et al., 2023) analyze the unresolved tension surrounding “fair use” in foundation-model training and underscore the lack of transparent disclosure about datasets. Sector-specific governance, meanwhile, emphasizes context-sensitive obligations. In healthcare, trustworthy AI depends on auditable pipelines and human-in-the-loop validation (Wiens et al., 2019). Earlier lessons from ambient-intelligence research show that pervasive computing often erodes privacy by default, a dynamic now resurfacing as AI systems extend into edge and IoT environments (Wingarz et al., 2024). Together, these issues illustrate a widening legal and technical mismatch where regulations define goals but lag behind in terms of the technical capabilities to properly enforce.

The Case for Trustworthy AI

Despite the rapid advancements in AI, key studies continue to expose persistent gaps, highlighting the need for stronger integration between ethical principles, technical frameworks, and the practical realities of deploying AI systems with fairness and accountability.

Healthcare is often positioned as a flagship domain for trustworthy AI because the stakes are exceptionally high (i.e., patient safety, equity of care, and clinical decision support). Diagnostic systems powered by computer vision and LLMs promise faster triage, earlier detection, and more efficient workflows. Yet these benefits are tempered by recurring problems of bias and accountability. For instance, studies demonstrate imaging models trained on narrow demographic cohorts underperform on underrepresented populations, thereby reinforcing existing health inequities (Saleh & Tabatabaei, 2025). The sector has begun developing targeted frameworks, such as model input-output traceability and mandated human-in-the-loop validation, to safeguard deployment. Nonetheless, practical challenges remain. Validation datasets rarely capture the heterogeneity of real-world patients; explanations intended to assist clinicians often prove too complex or too shallow; and integrating oversight into resource-constrained healthcare systems can be burdensome. Trust in healthcare AI therefore depends not only on fairness-aware training pipelines but also on adaptive evaluation protocols that ensure consistent performance across diverse settings and populations.

Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) embody both the promise and the uncertainty of trustworthy AI. On one hand, AVs offer the potential for improved safety by reducing human error. On the other, each failure is highly visible and often catastrophic. While advances in robustness, perception, and decision-making may continue to reduce crash rates in controlled environments, yet questions of liability and accountability remain unresolved. If an AV system causes harm, should responsibility lie with the developer, the manufacturer, or the end-user? Legal scholars note that consent-based liability frameworks remain fragile, as courts may reject driver agreements made through digital interfaces if users cannot demonstrate genuine understanding of the system’s risks and responsibilities (Pattinson et al., 2020). Moreover, validation remains limited. Most testing is done in simulation or under narrowly defined conditions, which may not capture the edge cases encountered on public roads (Kalra & Paddock, 2016). Therefore, the challenge is not only engineering safer models but aligning engineering practices with legal frameworks and societal expectations. Until these dimensions are integrated, the trustworthiness of AVs will remain contested.

Generative AI illustrates how technical advances often outpace governance. Large-scale text-to-image and text-to-text models are increasingly embedded across creative industries, education, and public sector. These systems demonstrate remarkable fluency and creativity, yet they also produce misinformation, offensive stereotypes, and synthetic media that undermine public trust. Initiatives such as the TrustGen benchmarking platform (Huang et al., 2025) mark a promising step toward systematically assessing generative foundation models across fairness, robustness, and safety dimensions. However, assessments reveal persistent weaknesses in multilingual prompts, edge cases, and malicious inputs. Legal debates compound these challenges. Unresolved questions of copyright and “fair use” in model training datasets leave developers and deployers in a precarious position (Henderson et al., 2023). Current mitigations, such as watermarking or traceability metadata, are useful but incomplete. The case of generative AI illustrates both the necessity and the difficulty of operationalizing trust. Without robust evaluation and enforceable governance, deployment risks are outpacing accountability.

Surveillance and Facial Recognition Technologies (FRTs) have long been a flashpoint in debates on ethical and trustworthy AI. Used in law enforcement, security, and commercial applications, FRTs promise efficiency but consistently exhibit higher error rates for women and minority groups. Progress in debiasing algorithms and diversified datasets has narrowed but not eliminated these disparities (Mitchell et al., 2021). Moreover, the use of FRTs raises concerns about ethics and civil liberties. Widespread surveillance threatens privacy norms and risks chilling effects on democratic participation. Several jurisdictions, such as San Francisco, California, have responded with moratoria or outright bans, illustrating how governance intervenes when technical fixes lag. Yet global adoption remains uneven, with authoritarian contexts deploying FRTs with minimal transparency or oversight. This case underscores that trustworthiness is not solely a function of model accuracy. Even if error rates were equalized, societal trust would still hinge on legitimacy, consent, and proportionality.

Table 2 illustrates trustworthiness challenges across multiple domains. Each domain demonstrates tangible technical progress while exhibiting enduring ethical, legal, and operational gaps that hinder reliable deployment modern day AI systems.

Table 2. Trustworthiness Gaps Across Multiple Domains

| Domain | Technical Progress | Persistent Gaps |

|---|---|---|

| Healthcare | Diagnostic support, traceability frameworks | Bias across demographics, ineffective explanation, limited workflow integration capabilities |

| Autonomous Vehicles (AVs) | Improved perception and safety under controlled conditions | Legal liability and accountability ambiguities, limited edge-case validation |

| Generative AI | Creativity, benchmarking platforms | Misinformation, IP/legal uncertainties, incomplete provenance metadata |

| Surveillance and Facial Recognition Technologies (FRTs) | Accuracy gains, dataset diversification | Demographic bias, civil liberties concerns, uneven governance |

The Pursuit of a More Responsible AI

The following emerging areas of AI illustrate how both technical innovations and institutional responses are adapting to the evolving demands of trust in the era of foundation models. The pursuit of ethical and responsible AI systems has catalyzed new work across disciplines, focusing not only on improving model reliability, explainability, and fairness, but also on strengthening the surrounding governance structures, oversight mechanisms, and regulatory frameworks. Together, these trends signal a movement toward a more holistic, systemic approach to trustworthy AI.

Mechanistic Interpretability and Causal Abstraction

As foundation models scale into the hundreds of billions of parameters, interpretability research has shifted from local approximations toward mechanistic understanding. Recent work establishes a theoretical framework for causal abstraction, aiming to map internal representations to human-interpretable concepts (Geiger et al., 2025). Despite challenges, this line of research is promising because it moves beyond proxy explanations toward structural insight. Causal mappings are fragile across tasks and current methods rarely scale beyond small models or limited modules. Moreover, even when abstractions are identified, translating them into actionable governance mechanisms or user-facing explanations remains an open problem.

Fairness in Federated and Distributed Learning

Situated at the crossroads of advanced technology and growing privacy demands, federated learning (FL) leverages a distributed framework to enable collaborative model training among multiple clients while safeguarding sensitive data. Despite its promise, the deployment of FL systems faces fairness challenges driven by various forms of heterogeneity, which can introduce bias, degrade model accuracy, distort predictions, and slow down convergence. Fairness-aware aggregation rules and personalized models could mitigate these effects, yet scaling these methods across large, dynamic federated networks remains difficult (Mukhtiar et al., 2025).

Human-Centered and Layered Explainability

Research is moving toward explanation systems that are adaptive, layered, and audience aware. Frameworks propose embedding explanatory mechanisms within models, tailoring outputs to user expertise, and incorporating feedback loops that refine explanation delivery (De Silva et al., 2017). These developments reflect growing recognition that explanations are relational and context specific. Yet embedding such adaptability introduces new risks. Explanations optimized for usability may sacrifice faithfulness, while those faithful to internal mechanics may overwhelm users with technical detail (Leiter et al., 2024). Privacy risks remain unresolved. As a recent scoping review shows, even partial explanations can leak sensitive information if adversaries probe explanation interfaces (Allana et al., 2025).

Benchmarking Ecosystems for Trustworthiness

The proliferation of generative and multimodal models has intensified the demand for trust benchmarks. Emerging platforms are beginning to address this gap by systematically testing models across robustness, fairness, and safety dimensions (Huang et al., 2025). These platforms reveal vulnerabilities in multilingual contexts, adversarial prompts, and minority representations, providing a more realistic picture of trustworthiness than conventional benchmarks. Yet the benchmarking ecosystem remains fragmented. No universally accepted standards for trust metrics yet exist, and benchmarks often lag emerging architectures and modalities. Furthermore, benchmarking remains resource-intensive, limiting adoption beyond major research labs.

Formal Verification for Foundation and Agentic Models

Formal verification roadmaps propose combining symbolic specification tools, such as interactive theorem provers including Coq and Isabelle(Lu et al., 2024; Lin et al., 2024) and model checking, with generative models to constrain outputs or validate compliance with safety rules. This hybrid approach is compelling because it aims to deliver verifiable guarantees for systems that would otherwise function as black boxes. Yet, even the most promising verification frameworks struggle with computational complexity, as recent studies show that while formal methods can yield provably correct explanations, their scalability remains severely limited for large or complex models (Ribeiro et al., 2022).

Researcher Attitudes and Evolving Norms

Recent surveys of AI researchers reveal a complex and evolving landscape of professional norms surrounding safety, risk, and responsibility. Research suggests that although AI experts urge global focus on AI safety, warning of existential dangers on par with nuclear war, work on AI alignment and catastrophic risk often faces skepticism. The study identifies two prevailing perspectives: one viewing AI as a controllable tool and another treating it as an uncontrollable agent. These divergent outlooks correspond to differing beliefs about the feasibility and urgency of safety interventions. Moreover, many experts express limited familiarity with core AI safety concepts such as instrumental convergence, suggesting that disagreement often reflects conceptual rather than purely ideological divides. Together, these findings illustrate that the research community’s internal pluralism continues to shape both discourse and policy engagement around responsible AI development (Field, 2025).

Table 3 summarizes the principal emerging trends in trustworthy AI. Each trend encapsulates the most recent research advances alongside unresolved challenges that define future inquiry.

Table 3. Emerging Research Trends in Trustworthy AI

| Trend | Research Advances | Open Problems |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanistic Interpretability and Causal Abstraction | Causal abstraction and internal concept mapping in foundation models | Fragile across tasks, limited scalability to large models |

| Fairness in Federated and Distributed Learning | Fairness-aware aggregation rules and personalized models for heterogeneous clients | Scaling FL across large, dynamic networks |

| Human-Centered and Layered Explainability | Adaptive, layered, and audience-aware explanation systems with feedback loops for refinement | Balancing faithfulness and usability; residual privacy leakage of sensitive information through explanations |

| Benchmarking Ecosystems for Trustworthiness | Domain-specific trustworthiness benchmarks | Fragmented evaluation standards; resource-intensive benchmarking pipelines |

| Formal Methods for Foundation and Agentic Models | Hybrid verification approaches combining SMT solvers and model-checking for safety compliance | Poor scalability; lack of automated specification tools and governance integration |

| Researcher Attitudes and Evolving Norms | Empirical mapping of researcher beliefs, value clusters, and conceptual familiarity with AI safety | Conceptual gaps and the lack of consensus on safety urgency and governance relevance |

The Unified Accountability Framework (UAF) for Trustworthy AI

Building upon the motivation established in this paper, the Unified Accountability Framework (UAF) is presented as a formalized approach to operationalizing trust in AI.

Below is a synthesis of the UAF’s five tiers, combining current best practices from academia, industry, and policy (e.g., EU AI Act, OECD principles, NIST AI Risk Management Framework).

Overview of the UAF

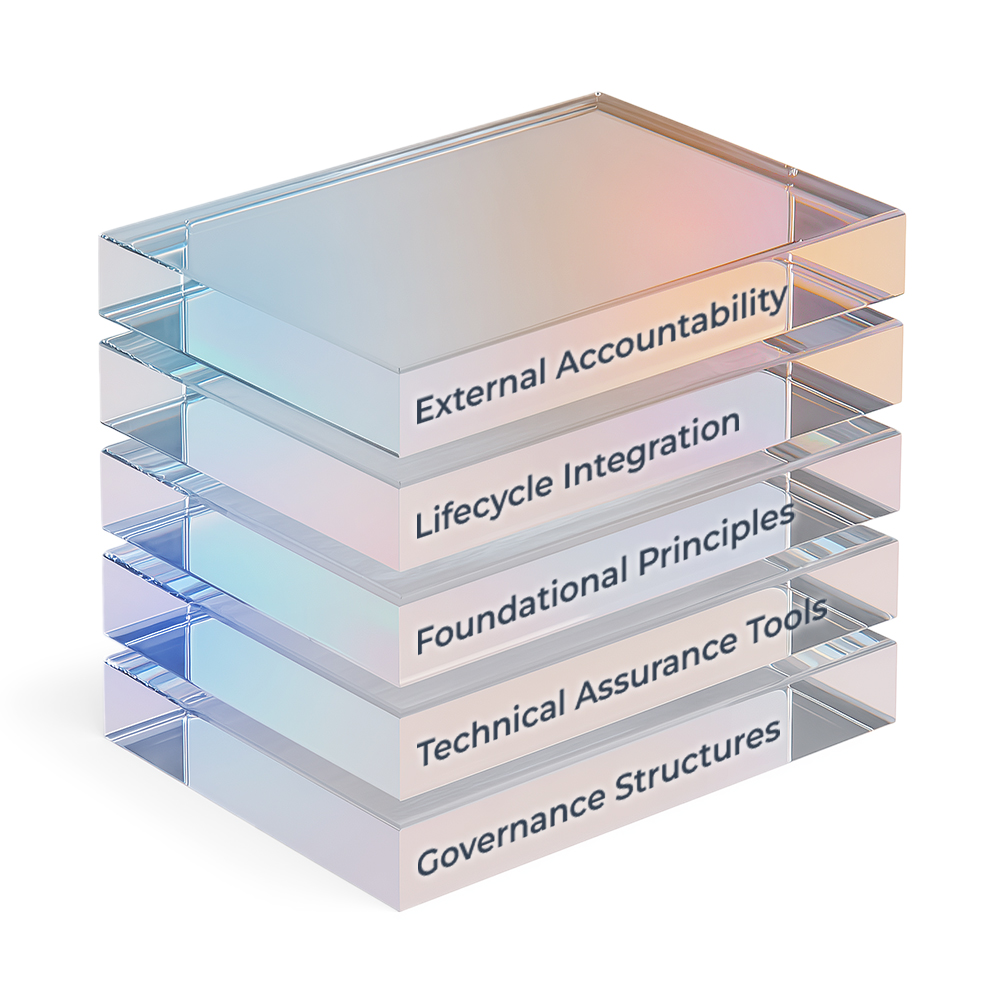

The UAF offers a comprehensive, 5-tier architecture designed to embed fairness, accountability, transparency, robustness, and human alignment throughout the full AI lifecycle. Existing approaches often isolate technical or ethical concerns to specific development phases (e.g., risk audits, fairness testing, or post-hoc evaluations). However, the UAF integrates technical, organizational, legal, and societal components into a coherent and actionable system. This unified approach is built not just to enforce compliance, but to engineer trustworthiness as a system-level property, making it measurable, monitorable, and adaptable over time. Figure 1 illustrates UAF’s 5 distinct tiers.

Figure 1: The Unified Accountability Framework (UAF) for Trustworthy AI with a 5-tier framework which includes Foundational Principles, Governance Structures, Lifecycle Integration, Technical Assurance Tools, and External Accountability.

Core Functional Mechanisms

The UAF is structured with five interdependent layers, each contributing to a system-wide foundation of trust. The 5-tier design is as follows:

- Foundational Principles. This base tier establishes the normative commitments that guide AI development and oversight. It includes commitments to:

- Human autonomy and dignity

- Fairness and non-discrimination

- Transparency and explainability

- Robustness and safety

- Accountability and auditability

- Privacy and data governance

- Sustainability and social benefit

- Governance Structures. To operationalize these principles, the framework embeds governance mechanisms within organizational workflows. These include AI ethics committees and boards, algorithmic impact assessments, cross-functional governance (legal, ethics, technology, product), clearly defined roles, documentation standards, and escalation pathways. These mechanisms ensure that ethical oversight is not peripheral, but integral to AI development and deployment.

- Lifecycle Integration. This tier applies ethical and governance commitments to each stage of the AI lifecycle:

- Problem Scoping. Use cases are defined with ethical KPIs and stakeholder impact assessments.

- Data Management. Processes include bias audits, data consent tracking, and privacy protections such as differential privacy.

- Model Development. Fairness-aware learning (e.g., adversarial debiasing), interpretability tools (e.g., SHAP (Lundberg et al., 2017), LIME (Riberio et al., 2016)), and robustness testing are applied to ensure reliable and explainable systems.

- Evaluation and Validation. Performance is tested across demographic groups and usage scenarios, including simulations of downstream risk.

- Deployment and Monitoring. Continuous monitoring for performance drift and failure modes, supported by human-in-the-loop controls.

- Post-Deployment Impact Evaluation. Systems incorporate real-world feedback, tracking of harms and benefits, and updating mechanisms for models and policies.

- Technical Assurance Tools. This tier codifies the use of validated technical tools and metrics. It includes explainability techniques, fairness metrics (e.g., demographic parity, equalized odds), robustness tools, and privacy-preserving techniques. These are embedded in MLOps pipelines with ethical checkpoints to ensure continuous validation.

- External Accountability. To maintain public and institutional trust, the final tier includes third-party audits, regulatory compliance mechanisms, transparency reporting, and participatory design practices. Public portals, open disclosure of incidents, and community engagement ensure alignment with societal expectations and democratic oversight.

A truly unified framework for operationalizing trust is not static. It must include built-in feedback mechanisms across all tiers. Learning, iteration, and adaptation are crucial as technology and society evolve. The unifying element therefore requires continual risk assessment, dynamic ethical goal realignment, integration of empirical post-deployment data, and responsive adaptation to regulatory and cultural shifts.

Table 4 provides a streamlined overview of UAF’s tiers, highlighting their primary focus areas and key components.

Table 4. Compact Summary of UAF

| UAF Tier | Focus | Key Elements |

|---|---|---|

| Foundational Principles | Ethical foundation for AI systems | Fairness, transparency, safety, accountability, privacy, sustainability, human dignity |

| Governance Structures | Organizational oversight mechanisms | Ethics boards, impact assessments, cross-functional teams, roles and responsibilities, documentation |

| Lifecycle Integration | Oversight integrated across AI lifecycle | Problem scoping, data governance, model fairness, evaluation, monitoring, post-deployment feedback |

| Technical Assurance Tools | Tools to validate system integrity | Explainability, fairness metrics, robustness testing, privacy-preserving methods, MLOps checks |

| External Accountability | Public and regulatory alignment | Third-party audits, compliance, transparency portals, participatory design, incident reporting |

Practical Implications

The UAF presents several transformative implications for organizations, regulators, and the broader AI ecosystem. First, it enables trust-by-design, embedding ethical and legal requirements into the core engineering pipeline rather than treating them as post-facto validations. This process facilitates proactive risk management and reduces the cost of compliance over time. Organizations implementing this framework are better positioned to meet evolving regulatory demands such as those outlined in the EU AI Act and NIST RMF.

Second, the framework offers a common operational language across disciplines. By integrating legal, technical, ethical, and product perspectives within a single governance architecture, it helps organizations overcome the silos that often impede responsible AI development. The inclusion of actionable tools, such as model specification, data sheets, and continuous evaluation pipelines, supports operational scalability without sacrificing oversight.

Third, the UAF reinforces public legitimacy and institutional accountability. The External Accountability tier ensures that AI systems are not only internally governed but are also externally auditable and responsive to societal expectations. Participatory design and open reporting mechanisms invite ongoing input from affected communities, which is particularly critical in domains with asymmetric power or high stakes decision-making.

Finally, this unified approach is inherently adaptive, positioning organizations to respond to rapid changes in technology, regulation, and public sentiment. Its feedback-driven structure ensures that AI systems evolve in alignment with human values and societal norms, enabling long term trustworthiness that is resilient, measurable, and context-sensitive.

Conclusion

As AI systems continue to scale in capability and reach, their influence over critical decisions in healthcare, finance, education, criminal justice, and public infrastructure demands a new standard of trustworthiness. The risks associated with opaque, biased, or unregulated AI are not abstract. They are real, measurable, and already impacting individuals and communities. In this context, building trust cannot be merely reduced to technical performance or regulatory compliance alone. It must encompass a holistic alignment between ethical values, system design, governance structures, and public accountability.

The Unified Accountability Framework addresses an operational integration gap by providing an integrated, end-to-end model for operationalizing trust across the full AI lifecycle. It bridges the gap between high-level ethical principles and concrete implementation through five interdependent tiers, ranging from Foundational Principles to Technical Assurance Tools and External Accountability. By adopting the UAF, institutions can more effectively navigate regulatory landscapes, foster cross-functional collaboration, and implement ethical safeguards without stifling innovation. Importantly, this framework supports continuous learning and adaptation, acknowledging that trust is not a one-time achievement, but a dynamic process shaped by evolving societal norms, technological change, and empirical outcomes.

Ultimately, the path to truly trustworthy AI lies not in fragmented solutions or reactive fixes, but in comprehensive, unified approaches like the UAF that integrate ethics, accountability, and technical excellence at every stage. As the foundation model era accelerates, frameworks of this type will be essential to ensuring that AI serves the public interest.

For policymakers, the UAF offers a structured approach for embedding enforceable accountability into regulatory design. For industry, it provides an actionable model for aligning product development with emerging global standards while maintaining agility. For researchers, it establishes a shared vocabulary that connects normative, technical, and institutional perspectives. Collectively, these applications position the UAF as a bridge between ethical theory and real-world assurance practice which is essential for trustworthy AI at scale.

ABOUT ENTEFY

Entefy is an enterprise AI software company. Entefy’s patented, multisensory AI technology delivers on the promise of the intelligent enterprise, at unprecedented speed and scale.

Entefy products and services help organizations transform their legacy systems and business processes—everything from knowledge management to workflows, supply chain logistics, cybersecurity, data privacy, customer engagement, quality assurance, forecasting, and more. Entefy’s customers vary in size from SMEs to large global public companies across multiple industries including financial services, healthcare, retail, and manufacturing.

To leap ahead and future proof your business with Entefy’s breakthrough AI technologies, visit www.entefy.com or contact us at contact@entefy.com.